How to lose your fear of the patient with pelvic pain and maybe change their life

In this opinion piece, we encourage GPs to treat the whole person with pelvic pain and not just the pelvis. It is important to listen and consider the impact the pain is having on the patient’s life. Painful periods can be treated with NSAIDs and hormones. A physiotherapist who specialises in pelvic pain is invaluable. A well-functioning bowel and lifestyle changes also improve pain. Providing pain education helps the patient to develop strategies to manage pain and improve their quality of life.

In this article, where we refer to ‘women’, we mean this in its most inclusive form, recognising that not all those assigned female at birth identify as women, but also not intending to generalise this advice to a patient assigned male at birth who experiences pelvic pain.

- Take some time to treat the whole person with pelvic pain, and not just the pelvis.

- Treat painful periods. NSAIDs are helpful for most patients and hormones should be considered early.Find a good physiotherapist in your area who specialises in pelvic pain, as most women with pelvic pain have pelvic floor dysfunction.

- Manage bowel function. Consider referring the patient to a physiotherapist, using aperients and optimising diet, exercise and fluid intake.

- Help your patient to understand what is happening in their body. The more they understand their pain, the more likely they are to develop strategies to manage their pain and improve their function and quality of life.

Recently, there has been an increasing focus on women’s pain, particularly endometriosis. This is welcome because, for so long, women with pelvic pain have been dismissed. The endometriosis focus is a double-edged sword, however, as focusing on one pathology may not be as beneficial as hoped. In focusing on endometriosis and validating a person’s pain experience with this diagnosis, we overlook all those with pain without endometriosis. It is also tempting to attribute all pain to endometriosis when it is found and forget the bigger picture – other viscera, the nerves, the musculoskeletal structures, the mind and the environment, thereby not adequately managing a person’s pain.

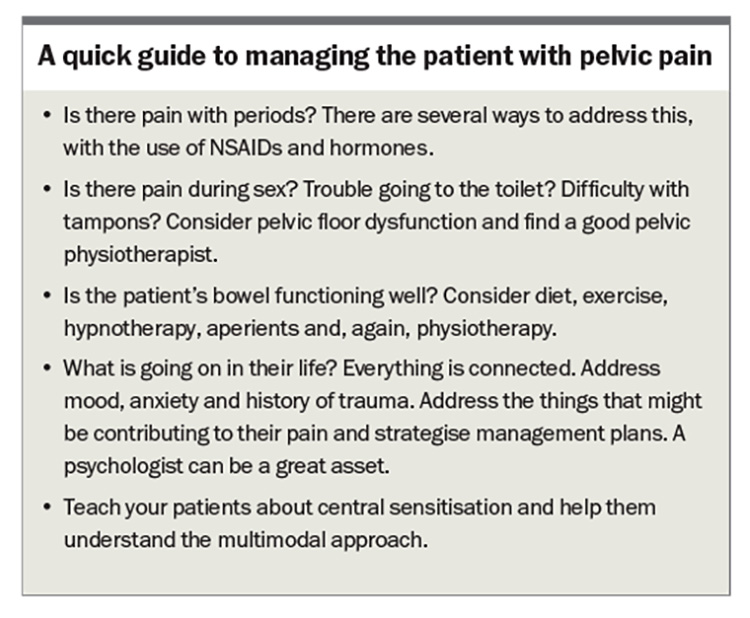

We need to be realistic when treating patients with pain. We may not ‘cure’ them of pain – just like we cannot cure asthma or diabetes – but many, if not most, can experience improved quality of life (see Box for a quick guide on managing pelvic pain).

This article offers ways to structure the extra time we might make early on to improve the patient’s experience and management of their pain.

What can we do for pelvic pain?

Pain is a universal sensation but we know that two people can have the same condition on physical or imaging findings but have a different experience of pain. We understand so much more now about why this is so. Pain is a complex experience that is influenced by many factors beyond the physical. It is influenced by past and current experiences, mood, sleep, cognitions, comorbid conditions, genetics and much more. Messaging within the spinal cord and brain can change to enhance or reduce an experience of pain – central sensitisation. To make an impact on persistent pain, all the potential impacting factors need to be considered and addressed. This is known as the sociopsychobiological approach.

It is important to listen and consider the impact the pain is having on the patient’s life – for example, are they missing work or school or is their relationship breaking down? Most people who have periods will have associated pain. But pain that stops someone living their life should not be dismissed. Let’s first consider period pain.

NSAIDs for period pain

For women with period pain, NSAIDs should be taken early, as soon as the pain or bleeding starts, or the day before if the cycle is regular enough to predict that. The first dose can be a double dose, then regular doses can be continued until they are no longer needed. Most people only need to take NSAIDs for a few days. There is no evidence that one NSAID is superior to another, so the choice depends on what works best for your patient.

Hormonal treatment

Many patients are concerned about using hormonal medications because they feel that using hormones is not natural. However, having a period every month from the age of 13 years to 50 years could also be considered ‘not natural’. For most of human history women have had far fewer periods. Women used to be older at menarche, then were pregnant and breastfeeding repeatedly for years and many died (often in childbirth) well before 50 years of age. We were not designed to sustain the repeated inflammatory process of endometrial shedding, and this can now be avoided with hormones, particularly if patients are experiencing pain.

Combined oral contraceptive pills (COCPs) are widely available and often effective in the treatment of pelvic pain. There are 16 different formulations available in Australia, mostly differing in the progestin component. There is no single best COCP. It is a process of trial and error to find one that suits your patient. Encourage your patient to trial each new pill for at least four months, unless there are intolerable side effects. A mood disturbance should not be dismissed, as it may be caused by progestin intolerance. Patients may need to trial several COCPs before finding one that suits them.

We recommend skipping the withdrawal bleed after the first month. There is no need to have a break every ‘x’ months, although breakthrough bleeding may occur. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne has a great online resource on how to skip periods and how to manage breakthrough bleeding (see: https://www.rch.org.au/kidsinfo/fact_sheets/Oral_

contraceptives_skipping_periods_when_taking_ the_Pill/).

For patients with migraine without aura, the COCP is fine to use. For patients with aura, a progestin-only pill, such as drospirenone, levonorgestrel, dienogest or norethisterone, can be tried (dienogest is not TGA approved for contraception). Cost may be an issue, as many hormonal therapies are not listed on the PBS.

For patients who do not want to take a pill, the etonogestrel implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, combined etonogestrel/ethinylestradiol vaginal ring, and levonorgestrel intrauterine devices are alternative options. If you suspect progestin intolerance, avoid depot medroxyprogesterone acetate unless the patient has already tolerated the oral version, as it cannot be removed or reversed. For patients with significant pelvic pain, consider referral for insertion of an intrauterine device under sedation or general anaesthetic.

If, at any point, you cannot find the right hormone therapy for your patient, consider referring them to a gynaecologist.

Other medications for pelvic pain

A low dose of a tricyclic antidepressant may be of benefit for pelvic pain. Consider 10 to 25 mg amitriptyline or another tricyclic (but use with caution if the patient has constipation) or a serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (e.g. duloxetine) or a gabapentinoid (e.g. gabapentin). Pregabalin should be avoided in women trying to conceive and in pregnancy because of the risk of congenital malformations. Evidence for the benefit of these agents for chronic pelvic pain is weaker than that for neuropathic pain, but it may be worth a trial. All of these medications are used off label in the management of pelvic pain.

Opioid prescribing should be avoided. If you go down this path, we cannot emphasise enough the importance of an opioid contract and the need to avoid the use of modified-release opioids.1

Physiotherapy

Eighty percent of women who experience pelvic pain will have pelvic floor dysfunction.2 Even without examining the pelvic floor, which takes time and is an intimate examination that may not be in your comfort zone or skill set, there is a lot that can be learnt from history taking alone. Pain during sex, difficulty using tampons, urinary hesitancy or trouble emptying the bowels are all red flags that suggest pelvic floor dysfunction. Consider finding a physiotherapist in your area who treats pelvic pain. Treating prolapse and incontinence are very different from treating pain, so ensure they have the right experience. If you cannot find a local physiotherapist, a number of physiotherapists provide telehealth services. Cost can be an issue. Consider a care plan to subsidise the visits. Some public hospitals will provide this service but not all, and there may be a significant waiting period. The Australian Government is now funding endometriosis and pelvic pain clinics in every state and territory in Australia (there are now 22 clinics across Australia; for more details see: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/endometriosis-and-pelvic-pain-clinics), which may also provide subsidised or bulk-billed physiotherapy. The Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia has a downloadable set of stretches that you can provide to your patient so they can get started straight away (see: https://www.pelvicpain.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Easy-Stretches-to-Relax-the-Pelvis-Stretches.pdf).

Bowels

We cannot understate the importance of a well-functioning bowel. Frequency and regularity are not enough to go by. Using the Bristol stool chart (see: https://www.continence.org.au/bristol-stool-chart) and asking the patient if they need to strain, whether they feel they have emptied completely and if there is any pain before, during and after a bowel movement can provide useful information. Irritable bowel syndrome is more prevalent in people with pelvic pain.

Bowel function can be optimised by referring the patient to a physiotherapist, using aperients and talking about diet and exercise with your patient. Adequate fluid intake is also important. Gut-directed hypnotherapy can help too; the best evidence for this is in people with irritable bowel syndrome.

Lifestyle factors

Diet, physical activity and social connection underpin our health, and these aspects of management need to be given adequate time and emphasis.

There is limited research into the role of the diet on pelvic pain, but a diet low in FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols), the Mediterranean diet, anti-inflammatory diets and a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids may help with pelvic pain. A varied diet that is plant based and avoids ultra-processed foods as much as possible is easy to follow. The full role of the microbiome, both in the gut and genital tract, will be established in time but the evidence so far suggests it is an important one and that we need to nurture it.

Input from a physiotherapist may be needed for exercise advice, but generally something is better than nothing, a little more is better than what patients are doing now and doing things they enjoy is better than doing things they do not. Graded activity is key in patients with pain, particularly those who have become deconditioned over time. This means start slow and go slow, sometimes really slow. Importantly, steer patients away from exercise that is core focused until they have the go ahead from their physiotherapist.

We know that lifestyle changes improve pain, including pelvic pain with and without endometriosis. There are also the added benefits of improved mood, sleep, libido, cardiovascular health and glycaemic control.

Environment

The patient’s environment is important. A single mother on a support pension who has depression and two high-needs children will need an approach that is going to work in her situation. Consider online options and if there are other support services that can assist. A patient with a high stress job may need to consider making some changes at work. Ultimately, these changes will be up to the individual, but exploring with them the factors that could be contributing to their pain and suffering, and the options available, may be valuable.

Psychology

Pain psychologists are important. Introducing the role of psychology to patients can be a delicate business at times. Although psychologists may help manage the effects of a person’s pain on their mental health and vice versa, they can also provide pain education, help identify triggers and contributing factors, and help the patient to develop strategies to manage their pain. Ideally, you want to find a psychologist who specialises in pain. Psychology Today Australia (see: https://www.psychologytoday.com) allows you to search by area of concern and find a psychologist who is local or who offers online consultations. If your patient is not keen on individual psychology or cannot afford this, online programs are available, for example MindSpot (see: https://www.mindspot.org.au/).

Pain education

The more pain education you can provide to your patient, the better. Good online resources are available to help demystify chronic pain. There may also be pain programs available at your local public hospital, but they may not always suit a patient with pelvic pain.

The Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia website has some great resources and a useful summary of the contributors to pelvic pain (see: https://www.pelvicpain.org.au/understanding-long-term-pelvic-pain/). The Neuro Orthopaedic Institute group from South Australia have some great online free and paid general resources (not pelvic pain specific), including the Explain Pain books and the Protectometer app (see: https://www.noigroup.com). Professor Lorimer Moseley at the University of South Australia explains how pain works and new approaches to help reduce pain in an online video (see: https://www.tamethebeast.org). The Agency for Clinical Innovation Pain Management Network has free general information, including ‘PainBytes’ for children and teenagers and ‘Our Mob’ for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (see: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/chronic-pain/).

The more a person understands what is happening in their body when they have pain, the more able they will be to develop strategies to manage their pain and improve their function and quality of life.

Pelvic pain and endometriosis

Although many patients with pelvic pain will have had a laparoscopy or possibly more than one, the advice given in this article still applies, regardless of the surgical findings. However, as almost all patients start their journey with the GP, many will not have had a laparoscopy when you first meet. There is much publicity around the seven-year delay to the diagnosis of endometriosis, but persistent pelvic pain can be diagnosed clinically if it has been present for more than three months and dysmenorrhoea can be diagnosed straight away. Early treatment of distressing symptoms with the methods described above is essential. Consider referral to a specialist if your patient experiences ongoing pain and functional impairment. The patient does not need a laparoscopy before treatment can begin. And these methods might just work for them.

The treatment of pelvic pain and endometriosis can be likened to that of treating other chronic pain conditions, such as chronic lower back pain. We know a herniated disc can occur without pain, and pain can occur without a herniated disc. The same is true of pelvic pain and endometriosis. Legitimise and validate your patient’s pain experience and address their concerns.

Summary

Taking the time to understand your patient with pelvic pain and having a low threshold for referral to a physiotherapist can be of significant benefit to the patient. Hormones have the best evidence in managing pelvic pain but some trial and error may be required to establish the right one. It is important to remember to treat the whole person, not just the pelvis. If needed, consider referring the patient to a gynaecologist with an interest in pain or a pain specialist with an interest in the pelvis. PMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Hunter Integrated Pain Service. Opioid treatment agreement 2013. Available online at: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/212760/HIPS-Health-professional-resources-opioid-treatment-agreement.pdf (accessed July 2024).

2. Marinkovic SP, Moldwin R, Gillen LM, Stanton SL. The management of interstitial cystitis or painful bladder syndrome in women. BMJ 2009; 339: b2707.