Trigeminal neuralgia: management in primary care

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a disorder characterised by recurrent unilateral brief electric shock-like pains that are abrupt in onset and termination. The pain is limited to the distribution of one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve and triggered by innocuous stimuli. Each patient with TN should be fully assessed and informed of the range of treatment options available to them.

- Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is characterised by the sudden onset of sharp pain on the side of the face, localised to the trigeminal nerve.

- TN has overlapping symptoms with common conditions, including dental conditions, cluster headaches, short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) and temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and should be considered as a differential diagnosis before any invasive treatment is undertaken.

- A range of treatment options are available to patients with TN, with pharmacotherapy being first line.

- Anticonvulsants, specifically carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, are the initial recommended choices of pharmacological treatment. Patients prescribed anti-convulsant medications should be monitored regularly for adverse effects including bone marrow suppression, liver function abnormalities and suicidality.

- Surgical treatment is considered second line and reserved for patients who experience adverse or diminishing effects of pharmacotherapy, taking into account a patient’s age and physical ability to withstand neurosurgery, and availability of surgical facilities.

- Nonpharmacological therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy and counselling, may help patients with TN to develop strategies to better manage their pain.

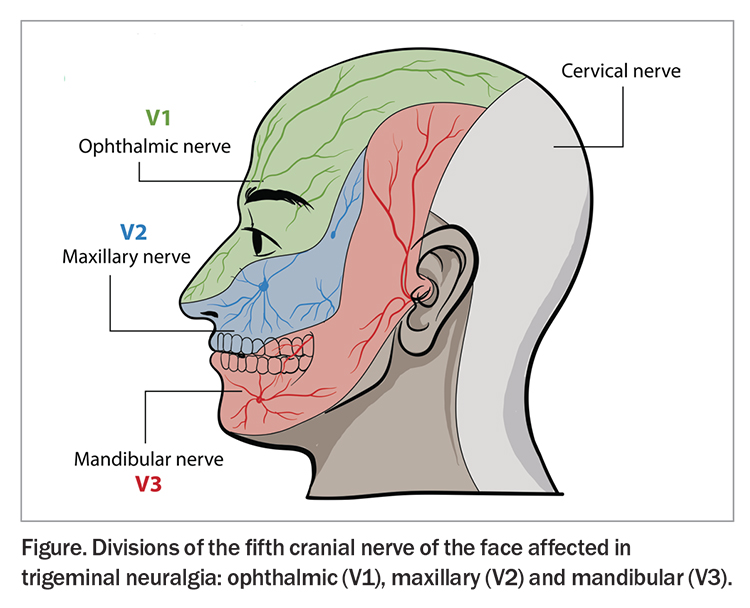

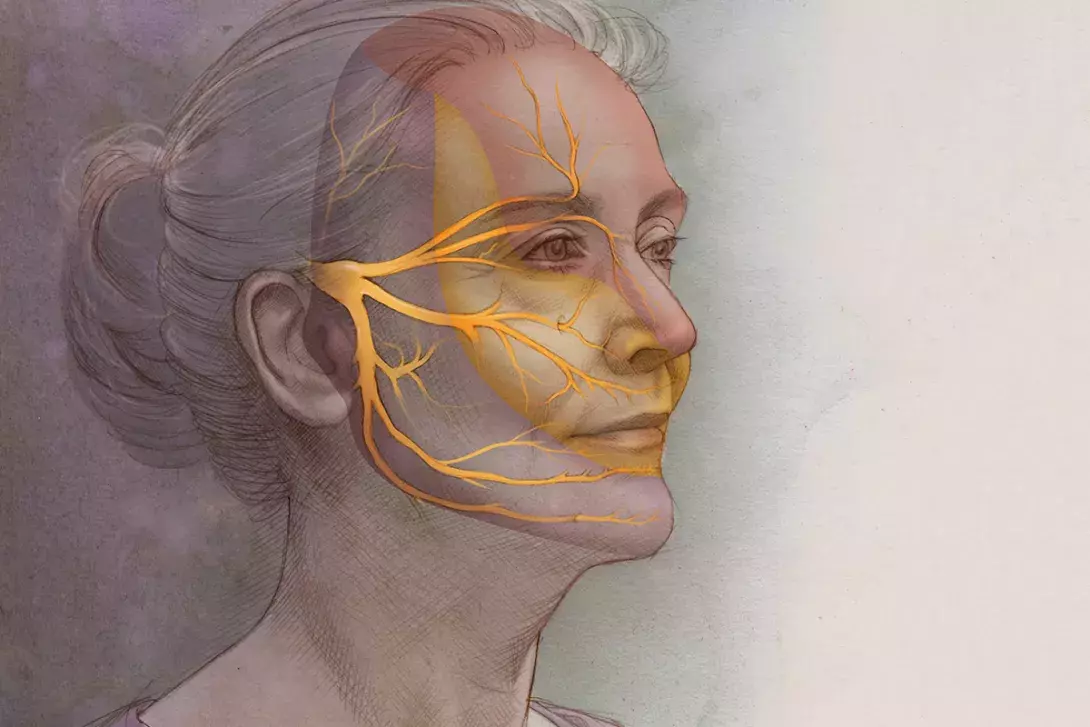

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is an uncommon neuropathic facial pain condition in the distribution of the fifth cranial nerve. This nerve has three divisions that supply sensation to the face: the maxillary (V2) and mandibular (V3), which are the most affected branches, and the ophthalmic (V1) branch, which is rarely affected (Figure). The pain is usually unilateral but may be bilateral.1 The International Association for the Study of Pain describes TN as ‘a manifestation of orofacial neuropathic pain restricted to one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve. The pain is recurrent, abrupt in onset and termination, triggered by innocuous stimuli and typically compared to an electric shock or described as shooting or stabbing’.2 The overall prevalence of TN in the general population is estimated at 0.015%, with a female to male ratio of 3 to 2. It most commonly develops in people over the age of 50 years, with one study showing a mean age of onset of 53 to 57 years and range of 24 to 93 years.3 TN can also occur in children; a recent study of a paediatric headache clinic identified five children out of 1040 aged between 9.5 to 16.5 years with TN.4

This article outlines the important diagnostic features of TN and discusses the available management options, including pharmacological, nonpharmacological and surgical.

Diagnosis

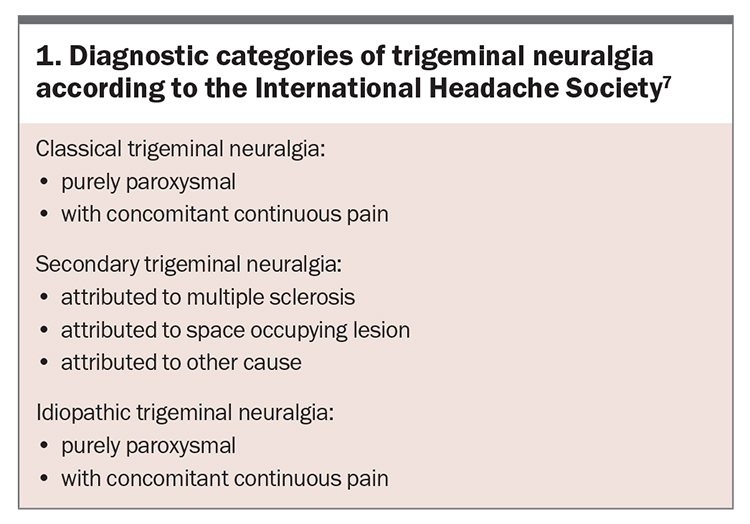

According to the International Headache Society, TN can be classified into one of three diagnostic categories (Box 1):5-7

- idiopathic TN is the most common form; no demonstrated microvascular compression is identified and there is no underlying disease or space-occupying lesions to account for the pain

- classical TN occurs due to neurovascular compression of trigeminal nerve roots as they exit the brainstem by the superior cerebellar artery, which causes focal demyelination at the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve

- secondary TN results from compression of the trigeminal nerve by a mass lesion such as: a tumour or arteriovenous malformations; intracranial ambormality due to conditions such as multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis or systemic lupus erythematosus; or injury of the nerve due to sinus or dental surgery.

MRI is the most effective imaging tool for detecting underlying causes. It can determine the relationship between blood vessels and the trigeminal nerve, such as the presence of microvascular compression. High resolution sequences through the trigeminal root entry zone increases the sensitivity of the imaging.

Symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia

Symptoms of TN include:

- sudden onset of sharp, stabbing pain to one side of the face

- pain confined to the distribution of the trigeminal nerve

- pain triggered or exacerbated by light touch, shaving, chewing, washing the face, applying makeup, brushing teeth or exposure in the mouth.

The typical or ‘classic’ form of the disorder (called ‘type 1’ or TN1) results in sudden electric shock-like pain that lasts anywhere from a few seconds to minutes, but can last up to two hours.8 Pain resolves completely between attacks. TN pain does not generally occur while asleep, which differentiates it from migraine headaches, which often cause patients to wake at night. There can be months or years between attacks, but for some patients, pain is not well controlled and can lead to a chronic trigeminal neuropathic pain syndrome.

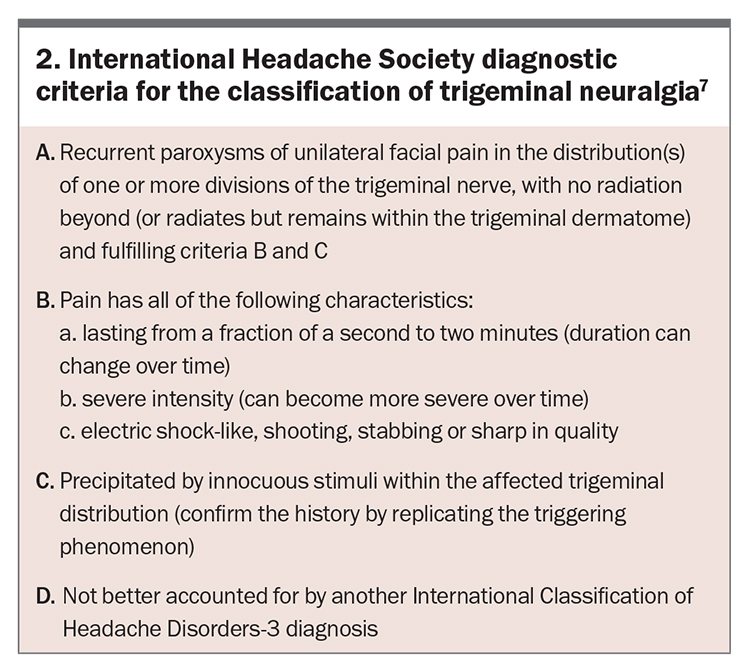

The ‘atypical’ form of the disorder (called ‘type 2’ or TN2) is characterised by constant, rather than intermittent, aching, burning or stabbing pain. The condition is not fatal, but can be very debilitating. Due to the intensity of the pain, some individuals may avoid daily activities or social contact because they fear an attack. Severe and recurrent pain caused by TN can lead to profound psychological effects such as depression and anxiety. The International Headache Society diagnostic criteria for the classification TN are summarised in Box 2.7

Differential diagnosis

Dental conditions, such as dental caries, pulpitis, dentine sensitivity, periodontal disorders, pericoronitis, cracked tooth syndrome and alveolar osteitis may mimic TN. Up to a quarter of patients will initially consult a dentist and 33 to 65% of TN cases may undergo unwarranted dental interventions. Invasive, irreversible dental treatment should not be performed without the dentist first carrying out appropriate clinical, and radiographic tests to exclude a nondental cause.9

Trigeminal deafferentation pain is trigeminal neuropathic pain caused by unintentional injury (trauma, tooth extraction). Generally, there is a constant burning or pulling sensation with a feeling of heaviness. There may be sensory disturbance on examination that, if caused by a medical procedure, is called ‘anaesthesia dolorosa’.10

Cluster headaches are characterised by short (15 to 180 minute) episodes of severe pain with associated ipsilateral autonomic symptoms, such as eyelid oedema, nasal congestion, lacrimation (tearing) or forehead sweating. Males are much more likely to be affected and the age of onset is generally before 30 years in 70% of patients.11,12 Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania is a similar headache to cluster headache but each episode of pain is shorter, lasting five to 20 minutes and the attacks are much more frequent at five to 20 per day.11,12

Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) is a syndrome characterised by attacks of pain that are unilateral and generally occur around the ocular area, with severe stabbing or electrical shock-like pain accompanied by prominent ipsilateral conjunctival injection and lacrimation.11,12 Each paroxysm of pain lasts between 10 to 120 seconds. The frequency of attacks may vary from one to 30 attacks per hour.13 Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headaches with autonomic features (SUNA) is a variant of SUNCT, without prominent lacrimation.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is a rare condition that is frequently mistaken for mandibular (V3) TN. Patients experience sharp pain in the tonsillar fossa, pharynx or base of tongue, which can radiate to the ear, angle of the jaw or upper lateral neck. Swallowing, yawning or talking increase symptoms, but chewing or touching the face does not precipitate an attack.14

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction occurs as a result of unbalanced activity (e.g. mastication due to loss of teeth), muscular spasm or overuse of jaw muscles (in nocturnal bruxism). Symptoms tend to be chronic. The most common symptoms include headache in 80% of cases; limited ability to open the mouth and facial pain on opening and closing the jaw in 40% of cases; radiation of pain from the joint to the ear causing pain in the front of or below the ear in 50% of cases; and TMJ crepitus.14 Other conditions that can mimic TN include post-herpetic neuralgia, post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy, atypical odontalgia, burning mouth syndrome and even maxillary sinusitis.

Management

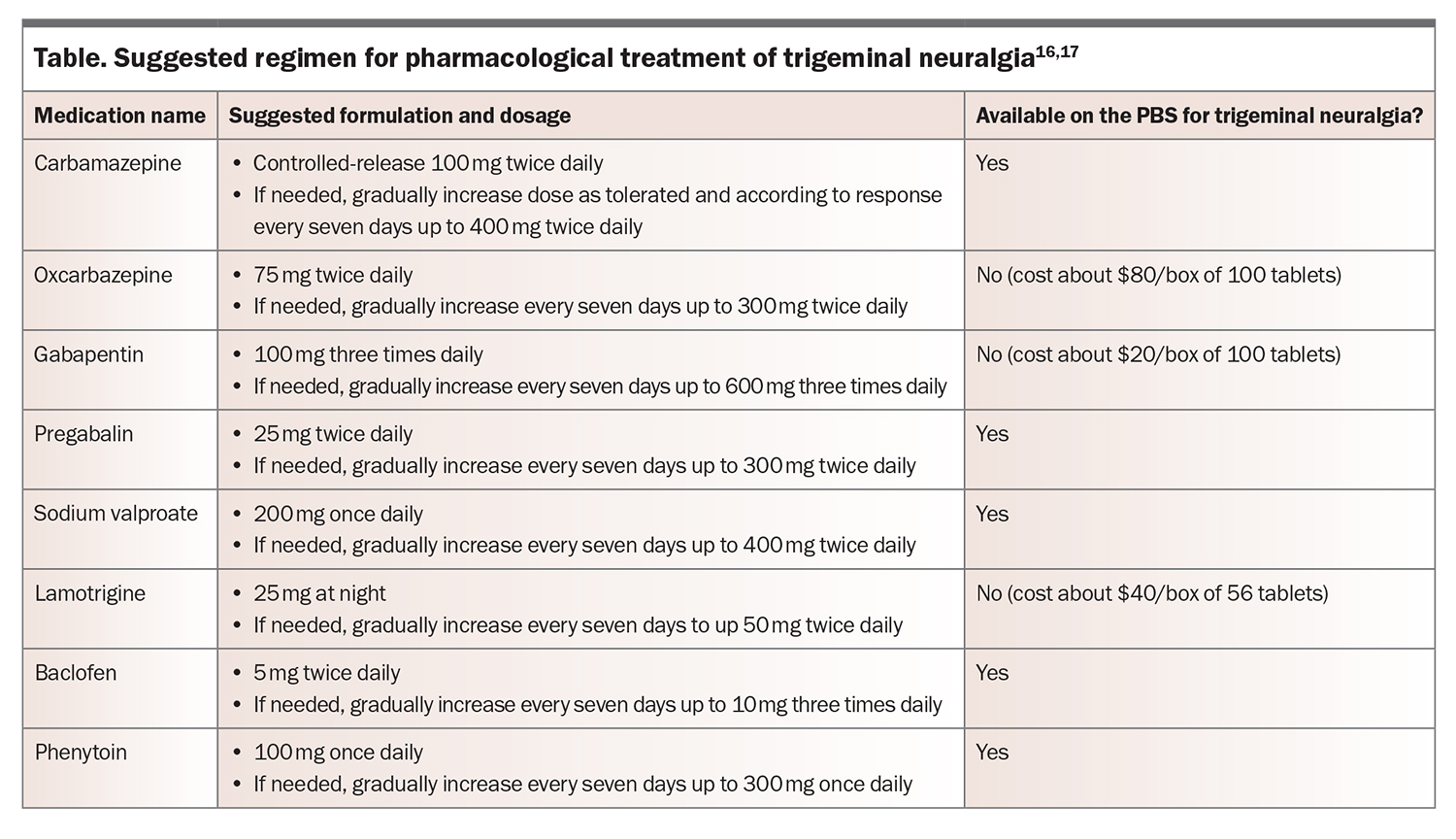

Pharmacotherapy is considered the first-line treatment for patients with TN, including for potential surgical candidates. Initially, treatment should be in the form of monotherapy; however combined therapy with different medications may be used when the response to monotherapy is poor or incomplete. Patients and, on many occasions, medical practitioners try to achieve rapid relief for severe pain, but it is important to avoid troublesome side effects that often result in premature cessation of a potentially effective medication. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that a ‘start low and go slow’ approach may be a more appropriate option in the long term.15 Options for pharmacological management of TN are outlined in the Table.16,17

Anticonvulsant therapies

Anticonvulsant medications have been used in pain management since the 1960s. They are useful for neuropathic pain, especially when the pain is lancinating or burning in nature. Anticonvulsant therapies are used to block nerve firing and are generally effective in treating classic TN (TN1) but often less effective in atypical TN (TN2). Current evidence suggests that pharmacotherapy should be initiated with carbamazepine as it has the greatest efficacy and lowest number needed to treat (NNT). In a systematic review of the effectiveness of antidepressants for neuropathic pain, carbamazepine demonstrated efficacy compared with placebo, with an NNT of 1.8 and number needed to harm (NNH) estimated at 3.4 for minor and 24 for severe adverse effects.18 The controlled-release formulation has fewer side effects than the immediate-release formulation. If carbamazepine causes troublesome side effects, discontinuing carbamazepine and replacing it with oxcarbazepine should be considered. Carbamazepine is highly specific for the relief of TN pain and therefore has a potential role as a diagnostic indicator for TN.

Carbamazepine should be introduced slowly, starting with the controlled-release preparation at 100 mg twice daily then increasing slowly by 100 mg every week, up to 400 mg twice daily if required. Potentially life-threatening conditions, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, occur more often in people of Asian descent who have the HLA-B15:02 and HLA-A31:01 alleles and are exposed to carbamazepine; therefore, it is advisable to test for both of these conditions before commencing patients on therapy.19

All patients treated with anticonvulsants should have baseline and six-monthly haematological, electrolyte and liver function tests, as bone marrow suppression can occur early and carbamazepine may cause significant hyponatraemia and liver function abnormalities. Some anticonvulsants increase the risk for suicidality and so careful follow-up of patients, particularly of at-risk individuals, should be maintained. Similarly, women in child-bearing years should be informed of the teratogenic potential of anticonvulsants.

Oxcarbazepine is an analogue of carbamazepine that is rapidly converted into its pharmacologically active metabolite and works by the same mechanism of action via voltage-gated sodium channels. Studies show it has similar efficacy to carbamazepine in the treatment of TN but greater tolerability, with less cognitive impairment, somnolence, dizziness, dry mouth and mood change, and fewer gastrointestinal symptoms and headaches.20 Oxcarbazepine is commonly used after a failed trial of carbamazepine or if tolerability is seen as a potential issue, such as in older people with comorbid disease and those taking multiple medications. Given the possibility of cross-reactivity with carbamazepine, if carbamazepine causes an allergic reaction, caution should be taken with the use of oxcarbazepine. In Australia, oxcarbazepine is not available on the PBS for the management of TN and needs to be funded privately by the patient.

Gabapentin is a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonist that acts primarily on presynaptic calcium channels of neurons to inhibit the release of excitatory neurotransmitters. Gabapentin is as effective as carbamazepine in the treatment of a number of neuropathic pain syndromes with a favourable side-effect profile of mild somnolence, dizziness, headache, confusion, nausea and ankle oedema. There are no known idiosyncratic skin reactions. Therapy is easy to initiate and drug interactions are few.21 Gabapentin is not available on the PBS for the management of TN and needs to be funded privately by the patient. However, the availability of generics makes this medication affordable.

Pregabalin is structurally related to gabapentin and was found to be effective in the treatment of patients with TN in a single, open-label study.22 It has analgesic, anticonvulsant, anxiolytic and sleep-modulating effects. Common adverse effects include dizziness, drowsiness, blurred vision, fatigue, weight gain, dry mouth, headache, impaired balance and peripheral oedema. Pregabalin is available on the PBS for the treatment of TN.

If the above medications are ineffective or patients develop intolerance, referral should be considered to a specialist for other treatment options including sodium valproate, duloxetine, lamotrigine, clonazepam, phenytoin and even levetiracetam.17,23-25

Antidepressant therapies

Antidepressant medications have also been used for over 40 years to manage neuropathic pain conditions. The mechanism of action of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) is independent of their antidepressant effect. However, these drugs have the potential for adverse side effects, including bothersome anticholinergic effects and life-threatening cardiovascular effects. In a Cochrane meta-analysis of antidepressants in chronic pain, the NNT was 2.9 (range, 2.4 to 4), with an NNH of 3.7 (range, 2.9 of 5.2) and NNT for major drug-related adverse effects leading to study withdrawal of 22.18

The main TCAs used in neuropathic pain are amitriptyline, which more strongly inhibits serotonin reuptake, and nortriptyline, which more strongly inhibits noradrenaline reuptake.26 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have only very limited evidence for an analgesic effect in trigeminal neuralgia. Serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine, which has an NNT of 3.1, and duloxetine, are better tolerated than TCAs; however, they are less effective.27

TCAs are illustrative examples of adjuvant analgesics for the following reasons:

- the effective analgesic dose ranges are lower (10 mg) than those for the primary indication (150 mg)

- although their onset of action for depressive symptoms may take two to three weeks, adjuvant benefits (i.e. analgesic effects) generally occur within three to four days

- adjuvant mechanisms of action (analgesia) are usually independent of, although sometimes synergistic with, primary effects (i.e. mood elevation).

Other pharmacological therapies

Opioid use in chronic nonmalignant pain states is controversial. Patients should be carefully assessed before starting long-term opioid therapy. Opioids should not be used as an alternative to comprehensive care, but rather should be integrated into a comprehensive care program when indicated. Once therapy has begun, patients on opioids need careful monitoring to detect and treat any adverse side effects and to ensure that patients improve. Assessment of patients on opioids requires the quantification and recording of specific criteria, including pain quality and intensity, activity level and functional capacity. Guidelines specify the conditions under which prescribing opioids is appropriate for the treatment of chronic pain.28 Opioids may increase pain by increasing central levels of protein kinase C and hence increasing central sensitisation.29

Baclofen, a strong GABA-B receptor agonist, is an important adjuvant for treating lancinating pain primarily through its inhibitory effect. Its use in TN has been mainly as an adjunct with carbamazepine because of its strong synergistic effect. Slow titration of baclofen is usually well tolerated and avoids potential side effects associated with CNS depression such as sedation, confusion, dizziness, nausea and postural hypotension.30

Studies have shown that injecting Botulinum toxin is a useful therapeutic tool in the management of refractory TN, and works by blocking activity of sensory nerves. Small doses of between 30 and 60 units are required, and the treatment effect using a standardised injection protocol can be effective and result in long-lasting pain relief.31

Nonpharmacological therapies

Despite the multiple therapeutic options available for the treatment of TN pain, some patients continue to experience pain. Therefore, approaches that improve a person’s ability to manage and cope with their pain are useful. Gains are usually confined to functional outcomes, such as improvement in mood and activity levels, rather than pain relief. Chronic pain from TN is frequently very isolating and depressing for the individual. Conversely, depression and sleep disturbance may render individuals more vulnerable to pain and suffering. Cognitive behavioural therapy programs may assist in the development of improved strategies for managing persistent pain. Some individuals benefit from supportive counselling with a psychologist to help them better understand and assess their pain and, if necessary, their readiness for surgery and ability to cope with potential outcomes.

Individuals may try to manage TN using complementary techniques, usually in combination with drug treatment. These therapies offer varying degrees of success. Some people find therapies such as yoga, mindfulness meditation or aromatherapy useful in improving pain management. Other options include acupuncture, chiropractic therapy, biofeedback, vitamin therapy and nutritional therapy.

The Trigeminal Neuralgia Association Australia provides support to people with TN and facial pain (https://tnaaustralia.org.au), and patients should be made aware of their local support group. The association has a number of local support groups across South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, and a separate incorporated body in Western Australia.

Acute therapy

Frequently, patients with TN present to the emergency department experiencing an acute attack of pain symptoms. Due to their distress, opioids such as morphine, codeine or oxycodone are usually administered, with limited success. If possible, patients should be advised to take an additional tablet of their prescribed anticonvulsant medication.

In presenting patients, although not proven in trials for TN treatment, anticonvulsants can be loaded intravenously (depending on availability), as follows:15

- phenytoin 10 to 15 mg/kg (about 1000 mg) IV slowly over at least 30 minutes

- levetiracetam 1000 mg IV over 15 minutes

- sodium valproate 10 mg/kg (about 1000 mg) IV over 30 minutes

- lacosamide 200 mg IV over 60 minutes.

Any patient given the above agents requires electrocardiography and blood pressure monitoring.

Surgery

Eventually, if medication fails to relieve pain or produces intolerable side effects, such as cognitive disturbances, memory loss, excess fatigue or bone marrow suppression, then surgical treatment may be indicated. An accurate diagnosis of TN is the most crucial point to clarify before considering a surgical solution for TN. In addition, high-resolution MRI greatly assists patients and healthcare providers in choosing between the different available surgical options. An editorial from the BMJ stated ‘Good surgeons know how to operate, better ones when to operate, and the best when not to operate.’ The benefits of any treatment should far outweigh the risk.32

Surgical options are generally considered as second line and are based on the patient’s response to and side effects from pharmacological management, their age and physical ability to withstand neurosurgery, and the surgical facilities available. Patients should be given concise and clear explanations of the potential surgical complications and alternative surgical procedures.

The surgical procedures for TN include gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery, percutaneous rhizotomy procedures and microvascular decompression (MVD).10 Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery is the only noninvasive technique, with the ‘surgical’ method involving focusing radiation rays on the ganglion or root in the posterior cranial fossa. The onset of pain relief is usually delayed by two months postoperatively, with more than 75% of patients experiencing pain relief lasting over two years.33

Percutaneous rhizotomy procedures, such as radiofrequency rhizotomy, provide immediate pain relief in over 97% of patients but this drops to about 10% at six months of follow up. Percutaneous balloon compression involves insertion and inflation of a surgical balloon catheter which results in physical injury to the trigeminal ganglion. About 82 to 93% of patients have reported immediate pain relief; however, 33% had a recurrence of pain after three years.34

MVD is universally accepted as a first-line surgical intervention for the classic form of TN in patients who are unresponsive to pharmacological treatment. It provides excellent immediate relief in 90% of patients post-operatively, with 80% remaining pain free by the end of the first year, 75% after three years and 73% after five years. The recurrence rate for patients with TN undergoing this treatment is 1% per year. Although MVD is the gold-standard neurosurgical procedure for TN, it carries a higher rate of more serious side effects and adverse events, and clinicians should ensure that patients are made aware of these before undergoing surgery.35

Conclusion

To date, no medical or surgical protocol has been found to be curative for most cases of idiopathic or classical TN. Each patient with TN should be fully assessed and informed of the range of treatment options available to them. A thorough discussion of the benefits and risks of each option should occur during this decision-making process. A discussion with a clinical psychologist may help patients to understand and assess their level of readiness for surgery and ability to cope with potential outcomes. Once pain is well controlled for a period of 12 months, a gradual reduction in the effective medication could be considered to see if the disease process has remitted, which is characteristic of TN. If pain does not recur, the patient may cease medication. If pain recurs, the previous medication regimen should be recommenced.

Finally, patients should be made aware of their local Trigeminal Neuralgia Association, which gives them the chance to discuss the condition and treatment options with other people in a supportive environment. PMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia – pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Pain 2001; 87: 165-166.

2. Scholz J, Finnerup NB, Attal N, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2019; 160: 53-59.

3. Lambru G, Zakrzewska J, Matharu M. Trigeminal neuralgia: a practical guide. Pract Neurol 2021; 21: 392-402.

4. Brameli A, Kachko L, Eidlitz-Markus T. Trigeminal neuralgia in children and adolescents: experience of a tertiary pediatric headache clinic. Headache 2021; 61: 137-142.

5. De Siqueira SR, Nobrega JC, Valle LB, Teixeira MJ, de Siqueira JT. Idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: clinical aspects and dental procedures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004; 98: 311-315.

6. Burchiel KJ. A new classification for facial pain. Neurosurgery 2003; 53: 1164-1167.

7. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1-211.

8. Bagheri SC. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with trigeminal neuralgia. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135: 1713-1717.

9. Bayer DB, Stenger TG. Trigeminal neuralgia: an overview. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1979; 48: 393-399.

10. Zakrzewska JM, Akram H. Neurosurgical interventions for the treatment of classical trigeminal neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; (9): CD007312.

11. Benoliel R, Sharav Y. Trigeminal neuralgia with lacrimation or SUNCT syndrome? Cephalalgia 1998; 18: 85-90.

12. Sjaastad O, Kruszewski P. Trigeminal neuralgia and "SUNCT" syndrome: similarities and differences in the clinical pictures: an overview. Funct Neurol 1992; 7: 103-107.

13. Pareja JA, Caminero AB, Sjaastad O. SUNCT syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. CNS Drugs 2002; 16: 373-383.

14. Drangsholt M, Truelove EL. Trigeminal neuralgia mistaken as temporomandibular disorder. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2001; 1: 41-50.

15. Dexter M, Aggarwal A. Medical, pharmacological and neurosurgical perspectives on trigeminal neuralgia. Aust Endod J 2018; 44: 136-147.

16. Haanpaa M, Attal N, Backonja M, Baron R, Bennett M, Bouhassira D. NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain 2011; 152: 14-27.

17. Attal N, Cruccu G, Haanpaa M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Nurmikko T. EFNS guidelines on pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13: 1153-1169.

18. McQuay HJ, Tramer M, Nye BA, Carroll D, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. Systematic review of antidepressants in neuropathic pain. Pain 1996; 68: 217-227.

19. Bendtsen L, JM Zakrzewska, Abbott J, et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on trigeminal neuralgia. Eur J Neurol 2019; 26: 831-849.

20. Di Stefano G, Truini A, Cruccu G. Current and innovative pharmacological options to treat typical and atypical trigeminal neuralgia. Drugs 2018; 78: 1433-1442.

21. Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. Pharmacotherapy of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain 2002; 18: 22-27.

22. Obermann M, Yoon MS, Sensen K, Maschke M, Diener HC, Katsarava Z. Efficacy of pregabalin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 174-181.

23. Shaikh S, Bin Yaacob H, Bin Abd Rahman R. Lamotrigine for trigeminal neuralgia: efficacy and safety in comparison with carbamazepine. J Chin Med Assoc 2011; 74: 243-249.

24. Pirapakaran K, Aggarwal A. The use of low-dose sodium valproate in the management of neuropathic pain: illustrative case series. Int J Med 2016; 46: 849-852.

25. Jorns TP, Johnston A, Zakrzewska JM. Pilot study to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of levetiracetam (Keppra) in treatment of patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Eur J Neurol 2009; 16: 740-744.

26. Fishbain D. Evidence-based data on pain relief with antidepressants. Ann Med 2000; 32: 305-316.

27. Hsu CC. Rapid management of trigeminal neuralgia and comorbid major depressive disorder with duloxetine. Ann Pharmacother 2014; 48: 1090-1092.

28. NSW Therapeutic Advisory Group Inc. Preventing and managing problems with opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain. NSW TAG: Sydney, 2015. Available online at: https://www.nswtag.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/pain-guidance-july-2015.pdf (accessed June 2023).

29. Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain 2010; 150: 573-581.

30. Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, Jensen TS, Sindrup SH. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence based proposal. Pain 2005; 118: 289-305.

31. Aggarwal A. ZAPTed (Zygomatic Arch and Point Triggers) protocol for botulinum toxin injections in the management of refractory trigeminal neuralgia. Clinical Medical Case Reports. July 2018; 1: 1-4.

32. Knowing when not to operate. [Editor’s Choice] BMJ 1999; 318(7180): 0. PMCID: PMC1114812.

33. Kondziolka D, Zorro O, Lobato-Polo J. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg 2010; 112: 758-765.

34. Frank F, Fabrizi AP. Percutaneous surgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1989; 97: 128-130.

35. Barker FG, Janetta PJ, Bissonette DJ. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 1077-1083.