Medication overuse headache: less is MOH

Patients with headaches often self-treat their pain with analgesics. Overusing any pain medications can lead to more frequent headaches, which in turn causes a separate headache disorder termed medication overuse headache (MOH). GPs are in a prime position to identify MOH and prevent the condition from occurring through patient education and use of appropriate preventive therapy.

- An estimated 3 million people live with migraines in Australia, with at least a quarter of them having medication overuse headache (MOH).

- MOH occurs when a patient with a pre-existing headache disorder has a headache on 15 or more days of the month, for at least three months, because of overuse of symptomatic headache medications.

- Any analgesic can contribute to MOH and lead to more frequent, disabling headaches that are more difficult to treat.

- Education, reduction in analgesic use and commencement of effective preventive treatment can improve headache frequency.

Medication overuse headache (MOH) is a type of secondary headache disorder in which the excessive use of pain medications (usually to treat primary headache disorders) can lead to further headaches.1 MOH has a worldwide prevalence of 1 to 3% in the general population.2,3 In Australia, it is estimated that there are 3 million people living with migraines and at least a quarter of them have MOH.4 MOH has also been known as drug-induced headache, medication misuse headache and rebound headache.1 MOH occurs when a patient with a pre-existing headache disorder has a headache on 15 or more days of the month, for at least three months, because of overuse of symptomatic headache medications.1

Patients who have headaches often self-treat their pain before seeking medical attention. If this strategy fails at home, they usually present to their GP requesting more pain medication or ‘stronger’ pain medication. GPs are thus in a prime position to identify MOH and prevent the condition from occurring through patient education and use of appropriate preventive therapy. Unfortunately, if this serious condition is not recognised, it can lead to escalating analgesic use, which in turn causes more frequent headaches that are more disabling and less responsive to many preventive treatments.

This article aims to increase awareness about the common entity of MOH, its causes and the key steps in its management. Importantly, we hope to convey that:

- although some analgesics are worse than others, any analgesic can contribute to MOH

- MOH is a maladaptive process in the brain, it is not just a ‘rebound’ headache

- MOH is a separate issue to addiction.

What is MOH?

MOH develops in a patient with a pre-existing headache disorder, which can be any of migraine, tension-type headache, chronic cluster headache, new daily persistent headache and possibly secondary headache disorders.2 MOH is not thought to occur in patients without headaches who overuse pain medications.2 Furthermore, patients with pre-existing headache disorders may not realise that the use of pain medications for non-headache reasons, such as joint pain, can also contribute to MOH.

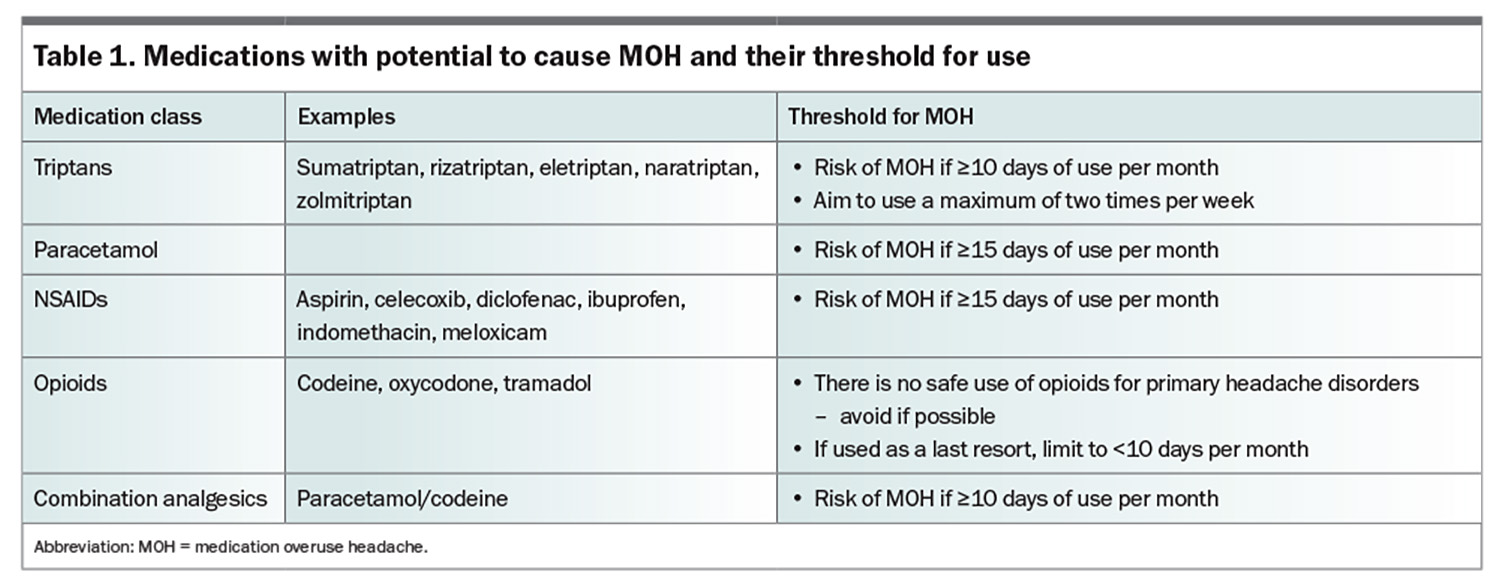

MOH should be considered in patients who have 15 or more headache days per month and are overusing acute analgesia. The definition of ‘medication overuse’ depends on the medication used (Table 1).1 There is still a lot we do not know about MOH. For example, we do not know how the cumulative daily dose of a medication impacts the risk of MOH.

MOH is a clinical diagnosis, with no specific history findings, examination findings, blood test results or scan results guiding the diagnosis.4 This is why the medication history is crucial, Patients suspected of having this condition find it beneficial to keep a pain medication diary to quantify how much of each medication is being taken on a monthly basis.

The pathophysiology of MOH is multifactorial. There is evidence that chronic exposure to pain medications can lead to:

- downregulation of the receptors and enzymes they work on, thereby requiring higher doses of analgesics to achieve the same analgesic effect5

- central sensitisation, whereby pain signals are amplified with a corresponding reduced pain threshold – both of which would exacerbate the headache2

- modulation of gene and protein expression involved in migraine pathogenesis2

- suppression of brainstem modulatory systems and increase in cortical hyperexcitability, lowering the threshold to induce pain and altering the perception of pain.2

Management of MOH

Prevention is the best treatment for MOH. Every patient with a primary headache disorder should:

- be counselled on the safe monthly limits of analgesics, in the same way they are counselled on safe daily limits

- be considered for preventive treatment if they have more than four attacks per month or disabling or difficult to treat attacks. This will give them the confidence to be able to to take their analgesic when needed

- have their acute treatment plan optimised, as effective early treatment limits the need for multiple days of medication use.

If a patient is diagnosed with MOH, there are several steps involved in managing the condition. It is important not to blame patients for excessive medication use and it can be helpful to educate patients that the disease is distinct from addiction, which can carry significant stigma. As patients are generally overusing medications out of necessity to manage unbearable pain, an empathetic approach can go a long way. It is important to strike a balance between the under-treatment of pain (which can occur if we deprescribe) and the overuse of medications for headaches, which can lead to worsening of pain.

There are five main steps in the management of MOH, which incorporate short- and longer-term goals for the patient. These five steps are:

- patient education

- safe cessation of offending medication(s)

- management of acute symptoms

- consideration of an appropriate preventive agent

- consideration of when to refer to a specialist or multidisciplinary chronic pain service.

Patient education

Education about the entity of MOH is crucial because many patients may not know that their pain medication has the potential to cause pain if it is taken inappropriately. Patients may find it hard to understand why their pain medication needs to be stopped for their pain to improve. Some patients may struggle to stop using the pain medication as they believe it to be ‘the only thing that helps with the pain’. As the treatment approach may seem counter-intuitive, adequate education is crucial to increase adherence with the treatment plan and to prevent relapse. Repetition of the information across multiple clinic reviews can be useful for knowledge retention.

Safe cessation of offending medication(s)

Withdrawal of the causative medication of MOH or significant reductions in its use will help patients with MOH. Medications such as triptans, paracetamol and NSAIDs may be abruptly stopped without a weaning period.5 Opioids may require a dose reduction before withdrawal, depending on the type and dose.6 Patients should be counselled that if they are stopping analgesic use abruptly, they can expect a transient worsening of their headaches, and this can be managed. In the much longer term, once MOH is ‘cured’, appropriate analgesics can be reintroduced, ensuring that they heed the safe usage recommendations presented in Table 1.

Management of acute symptoms

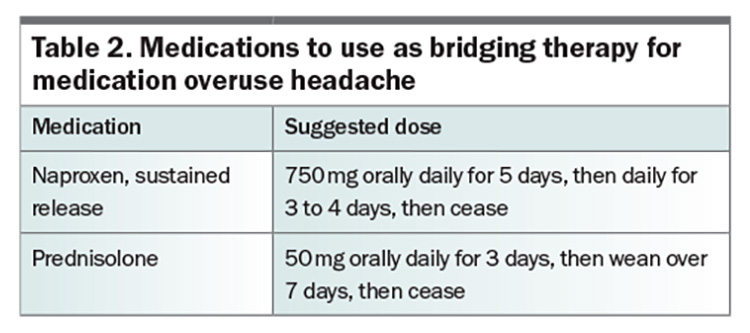

Patients may develop a worsening of their headaches on withdrawal of pain medications. In the experience of the authors, this can last up to two to three weeks, depending on the medication. In the community setting, there are several strategies that can help patients manage this transition (Table 2). In principle, if a patient is already overusing a particular class of therapy, it cannot be used as an effective bridging therapy (for example, you cannot bridge naproxen in the setting of ibuprofen overuse). Nonpharmacological therapy can also be useful to help patients through the worst of the pain once the offending agents have been deprescribed. For example, ice packs, heat packs, massage and meditation can be used to alleviate pain, either as an adjunct to bridging therapy or as an alternative to pharmacological therapy.

For some patients, their symptoms are too severe to allow successful withdraw of the offending medication. More advanced strategies include greater occipital nerve blocks by an appropriately trained clinician or hospitalisation and consideration of inpatient infusion.7 For most patients, however, we anticipate that MOH can be managed on an outpatient basis.

Consideration of an appropriate preventive agent

For patients who have more than four headache days per month, and for all patients who are overusing their acute analgesia, a preventive therapy should be considered in addition to stopping the offending medication.6 There are several resources that provide information on preventive therapy for migraine.8,9 It is important to trial preventive therapies at a reasonable dose for 8 to 12 weeks. As discussed above, because of the maladaptive processes, withdrawal of the offending agent gives patients the best chance to find the right preventer medication for them.

As with all headaches, it is also vitally important to address other reversible and lifestyle factors, such as inadequate water intake, sleep deprivation, high stress levels, sustained poor posture, eye strain from prolonged use of screens, teeth grinding and lack of exercise.

When to refer

Taking the steps above, and starting a preventive agent in complex cases, is helpful for all patients with MOH, even if specialist referral is required, as it gives the specialist a helpful base from which to work. Once MOH has been addressed and treated, patients who did not previously respond to symptomatic or preventer treatments may find them to be effective again.2 Early referral and input from a specialist may be useful for particular patient groups, such as those:

- with complex or multiple pain conditions, symptoms of dependence or high opioid use who may benefit from referral to a multidisciplinary chronic pain service or pain specialist

- with MOH who have not responded to the steps above who may benefit from referral to a neurologist.

A neurologist can also be helpful for patients with migraine who have failed to respond, or have a contraindication, to three lines of oral preventer therapy. These patients can be considered for use of advanced preventer therapies such as botulinum toxin type A or calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonists.10,11

Overall, prevention of MOH is better than cure. All acute pain medications can cause MOH. However, there is some evidence that the recently introduced oral small-molecule CGRP antagonists (the gepants, e.g. rimegepant and atogepant) may not cause MOH; therefore, patients who require frequent acute therapy (e.g. with triptans) may benefit from using gepants instead.12,13 Gepants are not yet PBS subsidised in Australia, so this approach is currently not financially viable for most patients.

As the management of MOH may be complex, a multidisciplinary approach involving GPs, community pharmacists, nurses and allied healthcare providers, with referral to neurologists/headache specialists (where available) for complex cases, is beneficial.14

Conclusion

It is important to be vigilant about the frequency and doses of acute medications used in patients with migraine to diagnose and treat MOH in a timely fashion. All patients with primary headaches are at risk of MOH so should have their use of acute medications checked periodically, even if their background therapy with preventers has not changed over years. By adopting a diligent approach, even in patients whose medication lists have not changed over time, we can ensure that the doses of these medications fall into a safe use pattern. PMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Stark has received honoraria, consulting fees or lecture fees from Abbvie, Pfizer, Teva, Lundbeck & Eli Lilly. Dr Ray has received honoraria for education presentations for Abbvie, Novartis and Viatris, has served on medical advisory boards for Pfizer, Viatris and Lilly, and his institution has received funding for research grants, clinical trials and projects supported by the International Headache Society, Brain Foundation, Lundbeck, Abbvie, Pfizer and Aeon. Dr Gunasekera: None.

References

1. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2018). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 38: 1-211.

2. Sun-Edelstein C, Rapoport AM, Rattanawong W, et al. The evolution of medication overuse headache: history, pathophysiology and clinical update. CNS Drugs 2021; 35: 545-565.

3. Russell MB. Epidemiology and management of medication-overuse headache in the general population. Neurol Sci 2019; 40(Suppl 1): 23-26.

4. Wijeratne T, Jenkins B, Stark RJ, et al. Assessing and managing medication overuse headache in Australian clinical practice. BMJ Neurol Open 2023; 5: e000418.

5. Williams D. Medication overuse headache. Aust Prescr 2005; 28: 59-62.

6. Diener HC, Antonaci F, Braschinsky M, et al. European academy of neurology guideline on the management of medication-overuse headache. Eur J Neurol 2020; 27: 1102-1116.

7. Ray JC, Cheng S, Tsan K, et al. Intravenous lidocaine and ketamine infusions for headache disorders: a retrospective cohort study. Front Neurol 2022; 13: 842082.

8. Prophylaxis for migraine. In: Therapeutic Guidelines, Melbourne. Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2019. Available online at: https://www.tg.org.au (accessed July 2024).

9. Ray JC, Macindoe C, Ginevra M, Hutton EJ. The state of migraine: an update on current and emerging treatments. Aust J Gen Pract 2021; 50: 915-921.

10. Ray JC, Kapoor M, Stark RJ, et al. Calcitonin gene related peptide in migraine: current therapeutics, future implications and potential off-target effects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2021; 92: 1325-1334.

11. Ray JC, Hutton EJ, Matharu M. Onabotulinumtoxin A in migraine: a review of the literature and factors associated with efficacy. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 2898.

12. Cheng T, Ray JC, Hilliard T, Stark RJ. Rimegepant – a new oral migraine medication. Med Today 2024; 25(1-2): 35-37.

13. Holland PR, Saengjaroentham C, Sureda-Gibert P, Strother L. Medication overuse headache: divergent effects of new acute antimigraine drugs. Cephalalgia 2020; 40: 889-891

14. Van Driel ML, Anderson E, McGuire TM, Stark R. Medication overuse headache: strategies for prevention and treatment using a multidisciplinary approach. Hong Kong Med J 2018; 24: 617-622.