A man with an injury to the left ankle and persistent pain

This case study highlights the management of ongoing pain arising from an ankle injury. Treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses the physical injury, subsequent pain and psychological aspects.

- The possible causes of ongoing pain following a lateral malleolus fracture must be considered and excluded.

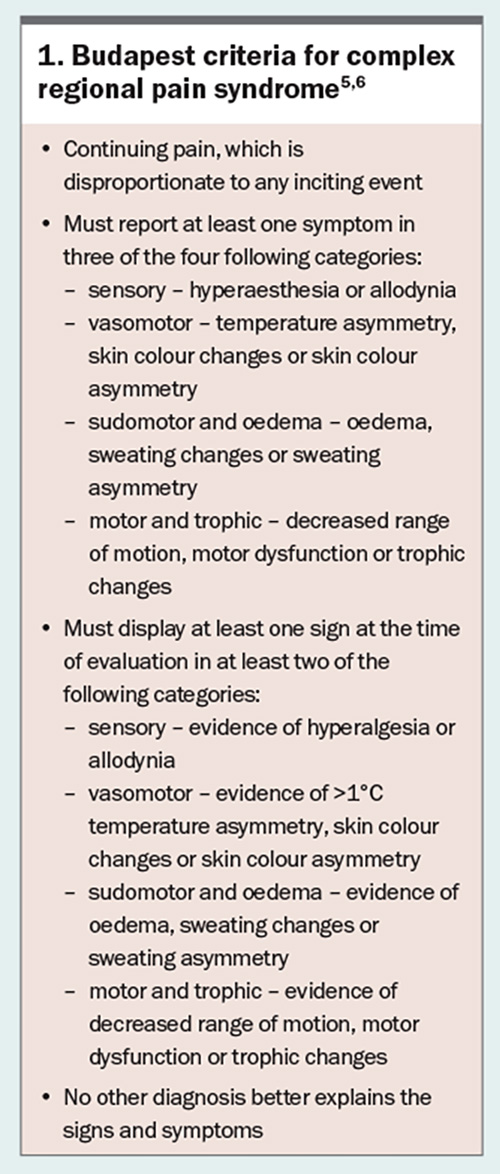

- Along with physical limb assessment, the Budapest criteria can help determine the presence of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). CRPS is the most likely cause of the ongoing pain in this patient.

- Management can involve pharmacotherapy, interventional treatments and graded motor imagery.

- A significant time commitment is required from the patient for treatment. Psychological aspects must also be considered and addressed.

Case scenario

John, a 43-year-old male construction worker, was injured when scaffolding being installed fell onto his left ankle on a Friday afternoon. He was sent home in a taxi. He spent the weekend in pain, unable to weight bear and could not return to work on Monday. He presented to the emergency department at his local hospital, where an x-ray revealed a fracture of the left lateral malleolus. Twelve weeks after the accident, he still cannot return to work because of pain and stiffness of the ankle joint. John consults with his regular GP in the presence of a Workers Compensation Case Manager, complaining of poor sleep because of pain requiring regular analgesia, difficulty in attending physiotherapy sessions and an inability to return to his former work. How should the GP proceed from here?

Commentary from orthopaedic specialists

By Dr Nicole Abdul, Dr Laura Beddard and Dr Andrew Wines

An isolated lateral malleolar fracture is a common injury following a twisting injury and accounts for 70% of all ankle fractures.1 A key part of determining if the injury is stable and whether it can therefore be treated nonoperatively is determining whether the deep deltoid ligament is intact. The best way of determining this is from a weightbearing anteroposterior ankle radiograph. If displacement of the fracture or widening of the medial clear space is not shown, the injury can safely be treated nonoperatively.1 The patient can fully weight bear in a removable boot for the first six weeks following the injury, after which they can gradually wean out of the boot. During the first six weeks, they can remove the boot to perform range-of-motion exercises, which will also reduce the risk of developing deep vein thrombosis. The expected outcome is that the fracture will heal and the patient will be able to resume their usual activity level without any residual pain.

John presents with postinjury pain and stiffness. In the first instance, the GP should take a history, examine the patient and arrange appropriate investigations before rereferral to an orthopaedic specialist. The possible causes of ongoing pain following a lateral malleolus fracture must be considered and ruled out.

Non-union of the fracture

Stable Weber B ankle fractures treated nonoperatively have a union rate of 99.2%.2 Risk factors for non-union include smoking, the presence of diabetes and the presence of peripheral vascular disease.3 Palpation of the fracture site provokes pain, and there may be mobility of the fracture fragments. The first-line investigation is a weight-bearing radiograph, which should show callus formation around the fracture site at 12 weeks postinjury. If there is doubt regarding union, a CT scan will confirm if the fracture has united. If the fracture has not united, an orthopaedic specialist would discuss the options of a period of immobilisation in a cast or operative management to fix the fracture.3

Ligamentous disruption or other missed injury

Although a ligamentous disruption or other fracture should have been excluded during the initial assessment, injuries may occasionally be missed. In a patient with ongoing pain, such as John, other injuries should be reconsidered. The patient may experience pain around the medial malleolus in the case of a deltoid ligament disruption, or between the tibia and fibula in a syndesmosis injury. A weight-bearing radiograph will help assess the alignment of the ankle joint and, if this is not conclusive, MRI may help to reveal malalignment and ligamentous injury.

Venous thromboembolism

In a patient who has not been weight bearing normally for several weeks, particularly if they have not been receiving venous thromboprophylaxis, the presence of a venous thromboembolism (VTE) must be excluded. The rate of VTE is very low (0.56%) in patients with isolated foot and ankle fractures, but the presence of Factor V Leiden, active cancer or prior VTE increases this risk.4 Signs on examination include lower limb swelling, pain in the calf, warm skin around the injury site, venous engorgement and limb erythema or discolouration. If VTE is suspected on examination, formal imaging, such as a duplex venous ultrasound scan, should be performed urgently. If there is any delay in the availability of an ultrasound scan, low-molecular-weight heparin to treat the suspected VTE should be considered until a scan can be performed.

Complex regional pain syndrome

Treatment for complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is difficult, as there is a limited understanding of the pathophysiology of the condition, there is no specific diagnostic test and the best treatment has not yet been established. The condition can occur following trauma, even when surgery has not been performed, as in John’s case. The Budapest clinical diagnostic criteria for CRPS can be used to aid diagnosis, recognising that the condition exists on a spectrum, as with other chronic pain syndromes, and that it is not essential to identify all components of these criteria before initiating management strategies (Box 1).5,6

A degree of central sensitisation is present if the pain is disproportionate to that expected, there is the presence of pain with burning or shooting characteristics or there is altered sensation to light touch (e.g. bedsheets at night), even if the patient does not fulfil all the criteria. Early treatment of CRPS is associated with the best outcomes. CRPS is best managed by referring the patient to a pain medicine specialist who may prescribe pharmacological agents and initiate physical and occupational therapy.6,7

Other considerations

In addition to investigating the causes of ongoing pain, care should be taken to address the patient’s psychosocial situation. After 12 weeks of an inability to return to work, and the pain disrupting activities of daily living and sleep quality, John should be assessed for conditions such as depression that might be having a negative effect on recovery. This is a sensitive subject and needs to be approached with appropriate care and treatment as needed.

The pain the patient experiences must also be addressed, and a careful pain history will reveal the analgesics the patient is taking and if these are appropriate. Analgesia can be started if necessary, and if the pain is particularly difficult to control, referral to a pain specialist should be sought.

John also reported difficulty in attending physiotherapy sessions, which may have a significant impact on recovery. The GP should investigate the reasons why John is finding it difficult to attend physiotherapy sessions and try to arrive at solutions to facilitate attendance. These solutions can include telephone consultations, referral to a physiotherapist closer to where he lives or assistance with transport to physiotherapy sessions. John should be encouraged to mobilise within the limits of pain, particularly with activities such as swimming, cycling or using a cross trainer, and referral for funding these activities may be needed.

Finally, he should be encouraged to discuss with his employer whether there is any work within the company that he could be transferred to while he is recovering, such as office-based work. This may only be a temporary measure but would help John resume paid employment until he can return to construction work.

Summary

Although relatively common, pain following an ankle injury is not an easy situation to manage, and care must be taken to ensure all possibilities for the patient’s pain are explored and treated. Treatment should be directed towards the initial injury and the broader psychosocial aspects also need to be explored and addressed to ensure complete recovery.

Commentary from a rehabilitation and pain medicine specialist

By Dr Clayton Thomas

A lateral malleolar fracture that is conservatively treated and is accompanied by ongoing severe pain, such as that in John’s case, is a common presentation to specialist pain medicine physicians. A diagnosis of CRPS is particularly considered. Usually, before referral, the patient would have undergone various investigations to exclude any orthopaedic complications of the injury, such as non-union of the fracture, a soft tissue ligamental tear, tendon injury or infection. If there are concerns of an infection, further blood tests, nuclear medicine scanning and other investigations may be required. Post-injury pain is common in the early period and can be an increasingly intrusive symptom. In any case, at the 12-week mark, it should be reasonably clear based on the history that something is significantly amiss.

John’s complaint about his inability to sleep because of his pain is significant. There are very few orthopaedic injuries, other than those complicated by CRPS, in which sleep is markedly disturbed because of pain. An inability to tolerate bed clothes on the affected limb would be part of the history. Complaints that the cast is too tight should also raise flags. A careful examination of the affected limb is required. The examination must exclude infection as a possible cause for the persistent pain in the early period once the cast has been removed. Thereafter, the aim is to determine if John has CRPS.

Assessment for CRPS

To determine if John has CRPS, both lower limbs should be examined carefully and the Budapest clinical criteria applied (Box 1).5,6 An infrared temperature sensor may also be used to determine any temperature differentials. The temperature may be either increased or decreased in the affected limb depending on the severity of the condition.7,8

Most (90%) patients with CRPS have CRPS type 1, in which no clearly identified nerve lesion is involved. A diagnosis of CRPS type 2 is confirmed if all the symptoms and signs of CRPS (according to the Budapest criteria) and clear nerve involvement are present, such as in cases of postcarpal tunnel decompression or De Quervain’s decompression with radial nerve involvement.7,8

It is essential that all aspects of the Budapest criteria are documented when the patient is first seen and examined. John has a workers compensation claim; trying to assess any patient many years later in a medicolegal setting can be extremely difficult if the initial consulting physicians have not documented all the clinical findings precisely. Documenting these findings against the Budapest criteria is essential, as they will change over time in patients with CRPS because of evolution of the condition and treatment.

John is diagnosed with CRPS and his case represents a typical presentation of CRPS. John reports that attending physiotherapy sessions aggravates his pain, which is also a common complaint in CRPS. The degree of hypersensitivity that occurs with movement can mean that even simple range-of-movement exercises can significantly disturb and aggravate the pain. If John has CRPS, he is more likely to be unable to fully weight bear using the affected limb. He is more likely than not to require the ongoing use of gait aids. The degree of hypersensitivity may also mean that he cannot wear enclosed footwear. If wearing enclosed footwear is possible, then a snug-fitting garment, not tight or loose, is more likely to be tolerated. A garment that rubs is likely to aggravate the pain. Even a firm fabric, such as denim, rubbing against the affected area could be disturbing.7,8

The primary diagnosis is made at the time of clinical presentation. Investigations are conducted primarily to exclude other causes of the persistent pain. However, it is possible to have two diagnoses present at any one time. For instance, there may be an arthritic joint plus CRPS. Given that John is relatively young, it is unlikely for evidence of significant osteoarthritis to be found in an adjacent joint. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment must be initiated immediately to improve his prognosis.

Pharmaceutical management

For John, a short course of prednisolone with low-dose amitriptyline is recommended. Prednisolone is a powerful anti-inflammatory agent, which may reduce any inflammatory components associated with CRPS. Amitriptyline has effects on central pain mechanisms, in addition to having sedative effects, and the dose may be increased depending on the benefit or side effects. A typical starting dose is 10 mg amitriptyline taken between dinnertime and bedtime; the next morning, depending on the side effects (particularly sedation), the dose may be uptitrated, if needed.

Interventional treatments

Given that John has acute CRPS, early consideration of interventional treatments would also be reasonable.9 Enlisting an interventional pain specialist to consider the use of lumbar sympathetic blocks or ketamine infusion may also be appropriate, although evidence on the benefit-to-harm ratio for these interventions varies. A referral for intervention depends on the severity of the CRPS and the accessibility of the treatment required. If a patient has a less severe form of CRPS and their functionality is less compromised, consideration of an early multidisciplinary pain management program is reasonable.

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation care

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation care involves a significant number of physical therapies provided by a physiotherapist or occupational therapist trained in the management of CRPS and with knowledge of central sensitisation and chronic pain.

Central sensitisation

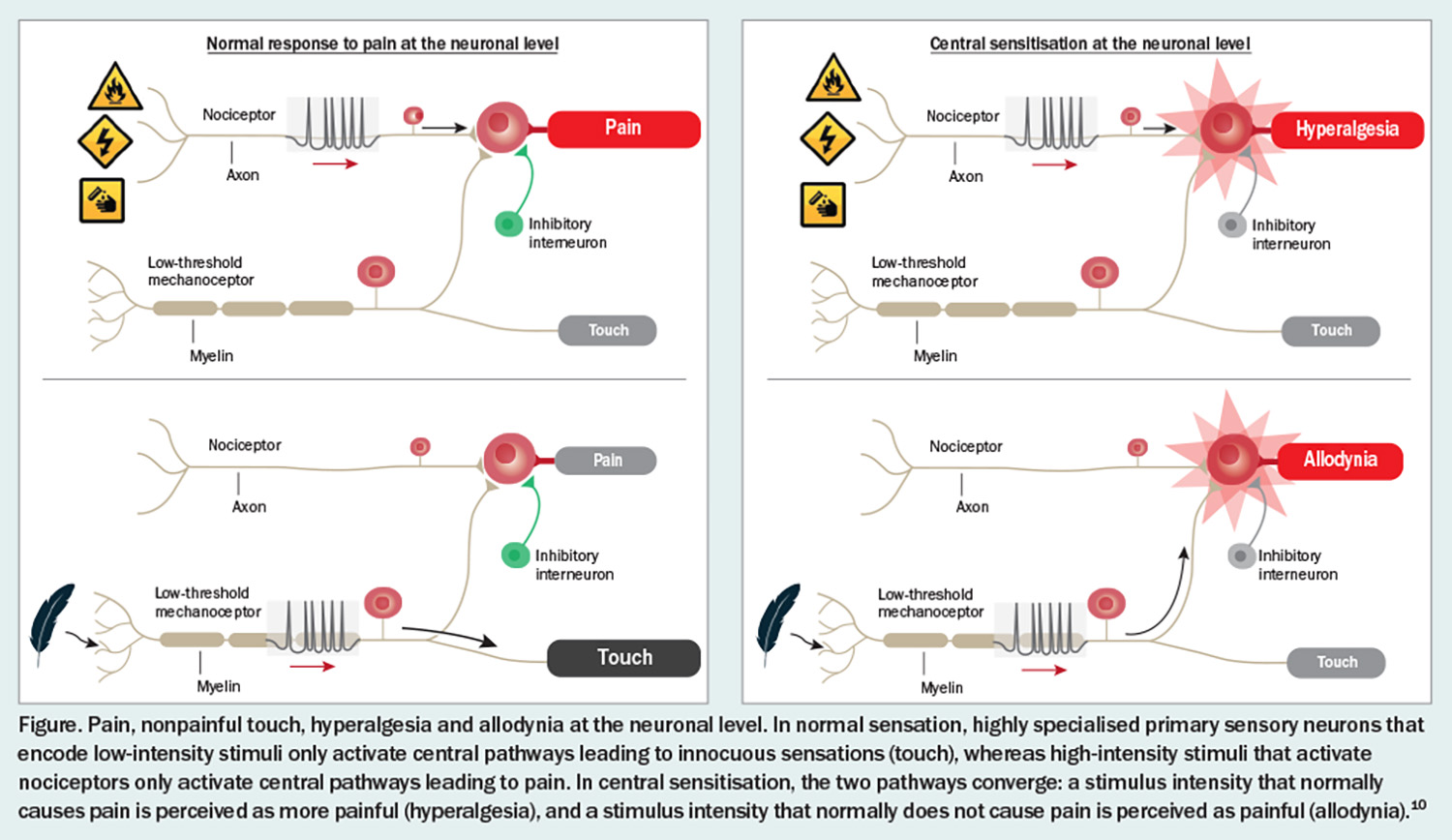

In normal sensation, the somatosensory system is organised such that the highly specialised primary central neurones that encode low-intensity stimuli only activate those central pathways that lead to innocuous sensations, whereas high-intensity stimuli that activate nociceptors only activate the central pathways that lead to pain.10 The two parallel pathways do not functionally intersect (Figure). Normal sensation is mediated by strong synaptic inputs among the particular sensory inputs and pathways and inhibitory neurons that focus activity to these dedicated circuits.

Central sensitisation is a disturbance of pain processing, initially put forward as a hypothesis by Professor Clifford Woolf, Professor of Neurology and Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School.10 In central sensitisation, somatosensory pathways show increases in synaptic efficacy and reductions in inhibition, which enhance the pain response to noxious stimuli in amplitude, duration and spatial extent.10 Meanwhile, the strengthening of normally ineffective synapses recruits subliminal input, such that low-intensity sensory inputs can now activate the pain circuits. The two parallel sensory pathways then converge.10

Chronic pain

Chronic pain from an organic perspective involves three different descriptors, or a combination of them, described as mixed pain.

- Neuropathic pain. This occurs when there is injury to a part of the peripheral or central nervous system.11 Chronic neuropathic pain cannot be defined without being able to determine which neurological structure has been damaged. Many patients misinterpret CRPS as being neuropathic. CRPS is not a neuropathic pain syndrome.

- Nociceptive pain. Chronic pain can also arise because of the persisting activation of nociceptors, such as what might occur with joint damage or inflammatory arthritis.11 CPRS is not a nociceptive pain syndrome.

- Nociplastic pain. In 2017, the International Association for the Study of Pain determined a third category, which is chronic pain being nociplastic (pain due to central sensitisation).11 Examples of nociplastic pain include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular joint disorder, tension headaches, painful bladder syndrome and CRPS. Patients with nociplastic pain syndromes usually respond to neuroactive compounds, which alter neurotransmission (some drugs derived from antidepressants and some from antiepileptic drugs) and are worsened by opioids, particularly prohyperalgesic opioids, such as oxycodone.

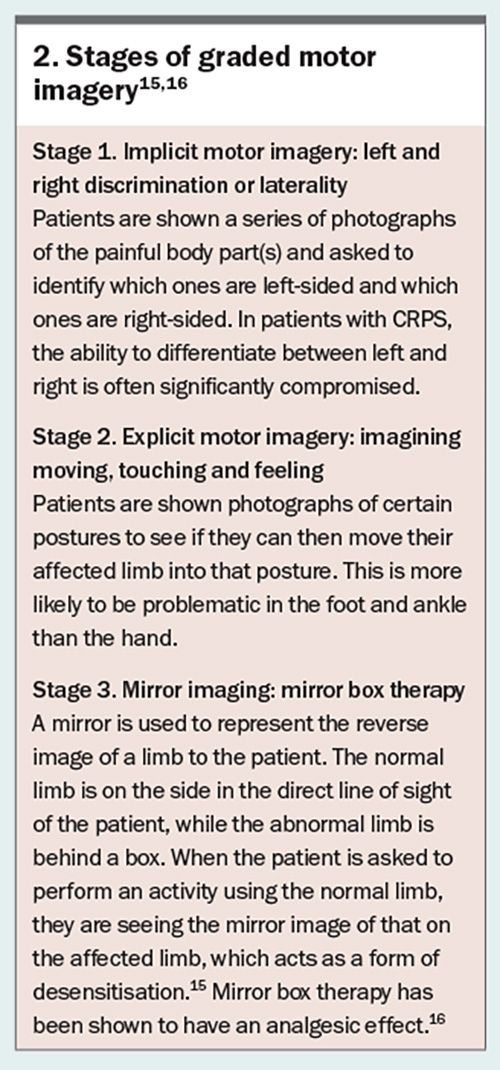

Graded motor imagery

For John, graded motor imagery is the main treatment. Graded motor imagery involves a sequence of strategies including laterality restoration (the ability to identify left and right limbs) using a mirror box.12-15 The treatment is effective for CRPS of any duration. The treatment includes three stages: implicit motor imagery, explicit motor imagery and mirror therapy (Box 2).15,16

Other considerations

As John progresses through treatment, the types of exercises performed should be carefully increased in the following sequence: performing part of the movement without inducing pain, performing part of the movement and inducing pain, increasing the frequency of the movement and increasing the strength of the movement. Finally, more weight-bearing activities should be introduced.

A significant time commitment is required from John. Spending 90 minutes to two hours per day would not be unreasonable in the early stages of treatment. The primary objective is for him to eventually manage his own rehabilitation. Patient buy-in is essential. Tactile discrimination training is useful for this purpose, as it allows the patient to witness the benefit of the treatment.16

In addition to the physical aspects of management, the psychological component of CRPS is essential to manage, which might include addressing depression, anxiety, anger, catastrophisation and fear of movement, among other issues. Hydrotherapy may also be used because of the weightlessness of the exercise. The soothing nature of water can help alleviate oedema in the affected limb.

Summary

CRPS is a medical emergency that requires a prompt referral from the diagnosing doctor. Treatment started early after diagnosis can help improve the patient’s prognosis. There are several treatments that may be considered to help manage the condition, including pharmacotherapy, interventional treatment, graded motor imagery and psychological therapy. The complexity of this condition makes urgent referral to a pain medicine specialist essential as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. PMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Abdul, Dr Beddard and Dr Thomas: None. Dr Wines is General Director and Treasurer of the Australian Orthopaedic Association; and Treasurer of the International Orthopaedic Diversity Alliance.

References

1. Gougoulias N, Sakellariou A. When is a simple fracture of the lateral malleolus not so simple? how to assess stability, which ones to fix and the role of the deltoid ligament. Bone Joint J 2017; 99-B: 851-855.

2. Kortekangas T, Haapasalo H, Flinkkilä T, et al. Three week versus six week immobilisation for stable Weber B type ankle fractures: randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority clinical trial. BMJ 2019; 364: k5432. Erratum in: BMJ 2019; 364: l457.

3. Capogna BM, Egol KA. Treatment of nonunions after malleolar fractures. Foot Ankle Clin 2016; 21: 49-62.

4. Gouzoulis MJ, Joo PY, Kammien AJ, McLaughlin WM, Yoo B, Grauer JN. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism following fractures isolated to the foot and ankle fracture. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0276548.

5. Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, Wilson PR. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med 2007; 8: 326-331.

6. Goebel A, Bisla J, Carganillo R, et al. Appendix 3, Research diagnostic criteria (the ‘Budapest Criteria’) for complex regional pain syndrome. In: A randomised placebo-controlled Phase III multicentre trial: low-dose intravenous immunoglobulin treatment for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome (LIPS trial). Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2017. (Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation, No. 4.5.) Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK464482/ (accessed July 2024).

7. Taylor SS, Noor N, Urits I, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther 2021; 10: 875-892. Erratum in: Pain Ther 2021; 10: 893-894.

8. Johnson S, Cowell F, Gillespie S, Goebel A. Complex regional pain syndrome what is the outcome? - a systematic review of the course and impact of CRPS at 12 months from symptom onset and beyond. Eur J Pain 2022; 26: 1203-1220.

9. Shafiee E, MacDermid J, Packham T, Walton D, Grewal R, Farzad M. The effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions on pain and disability for CRPS; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain 2023; 39: 91-105.

10. Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011; 152: S2-S15.

11. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Terminology. Washington, DC: IASP; 2021. Available online at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (accessed July 2024).

12. Dilek B, Ayhan C, Yagci G, Yakut Y. Effectiveness of graded motor imagery to improve hand function in patients with distal radius fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Ther 2018; 31: 2-9.e1.

13. Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Pain 2004; 108: 192-198.

14. Bowering KJ, O’Connell NE, Tabor A, et al. The effects of graded motor imagery and its components on chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain 2013; 14: 3-13.

15. Limakatso K, Cashin AG, Williams S, Devonshire J, Parker R, McAuley JH. The efficacy of graded motor imagery and its components on phantom limb pain and disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Pain 2023; 7: 2188899.

16. Longo MR, Betti V, Aglioti SM, Haggard P. Visually induced analgesia: seeing the body reduces pain. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 12125-12130.

17. Moseley GL, Wiech K. The effect of tactile discrimination training is enhanced when patients watch the reflected image of their unaffected limb during training. Pain 2009; 144: 314-319.