Prescription opioids: management of long-term use

The use of prescription opioids for chronic pain management has been associated with a rise in complications, including overdose deaths. Regulatory reform and monitoring have led to many patients having their opioids reduced or ceased without adequate consideration or management of symptoms and the consequences of their opioid dependence. All prescribers must ensure responsible opioid prescribing practice, including patient education to minimise harms and mitigate risks to their patients.

- Prolonged prescribing of opioid medication for chronic pain can lead to a range of negative outcomes for some patients, including opioid-induced hyperalgesia, opioid dependence and risk of overdose.

- Risk factors that predict prolonged use of opioid medication include a history of adverse childhood experiences, past substance dependence, mental health problems and adverse psychosocial factors.

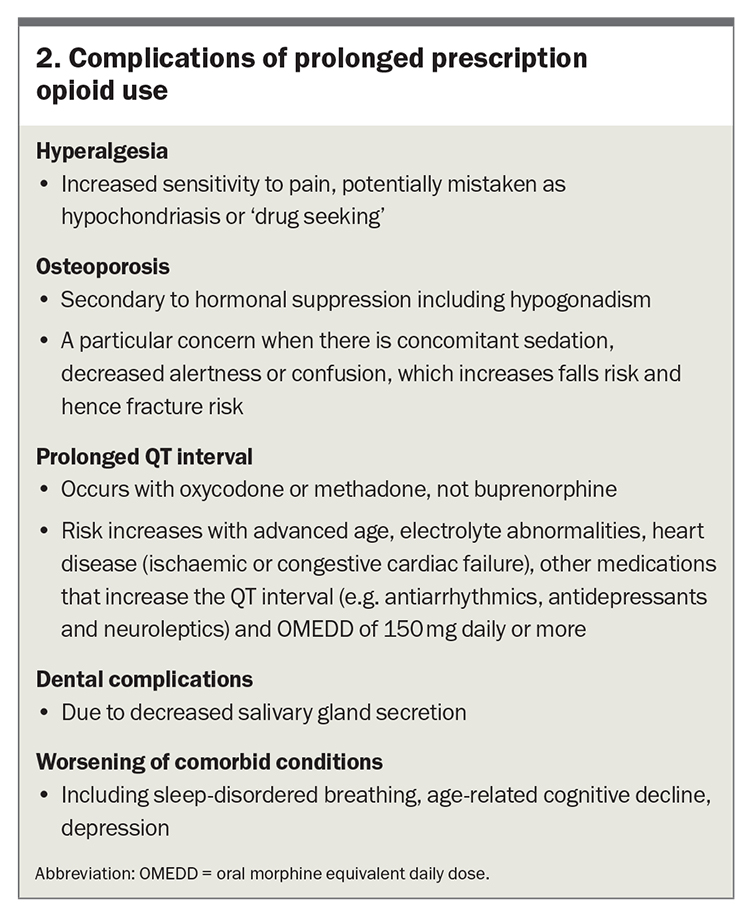

- Patients who have used opioids for a long time require appropriate assessment and management to minimise risks, including education about the possible complications such as overdose, hyperalgesia, osteoporosis, prolonged QT interval, dental complications and worsening of other comorbid conditions.

- Opioid dose tapering is commonly advised and may be fast or slow, with the rate being influenced by the level of risk.

- All health professionals have a role in reducing the adverse outcomes of long-term prescription opioid use through responsible practice in their approach to opioids.

One in five Australians experience persistent pain during their lifetime.1 Over past decades, the most commonly prescribed group of analgesics for persistent pain became long-term opioids. With this increase in prolonged use of opioids in the community, there was a rise in opioid dependence, opioid use disorder and opioid overdose deaths in many countries, including Australia.2 Today, opioids are the most commonly identified substances involved in drug overdose deaths, along with concomitant benzodiazepines and antidepressants.3

In an effort to reduce this trend, governments and health authorities have promoted education of health professionals and the community about the limitations and risks of prescription opioids, along with regulatory reform.4 In the US, a 2016 opioid prescribing guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) led medical practitioners to rapidly reduce or cease prescription of opioids in many patients.5 This resulted in increased pain, opioid withdrawal symptoms and patient distress, sometimes presenting as behavioural problems such as aggression and self-harm.6 In 2022, the CDC updated this guideline, advocating flexible patient-centred care rather than dosage thresholds across all patient groups.7

In Australia, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for deprescribing opioid analgesics released in 2023 include recommendations on opioid deprescribing in different patient groups.8 These include patients with chronic noncancer pain and chronic cancer-survivor pain where there is lack of benefit compared with baseline, lack of progress to therapeutic goals or intolerable side effects. This guideline suggests avoiding opioid deprescribing for people taking opioids with a severe opioid use disorder, rather suggesting evidence-based care with the potential for transition to medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.8

This article explores the negative effects of long-term use of prescription opioids and outlines recommended strategies to manage patients taking prescription opioids long term, including risk mitigation strategies.

Defining the prescription opioid ‘problem’

Although prescription opioids have a place in treating acute, and occasionally chronic, pain, long-term prescribing can be associated with a range of negative consequences and behaviours. These include opioid tolerance, risk of overdose and aberrant behaviour.

Opioid tolerance

In opioid tolerance, increasing doses of opioid are required by the individual to feel comfortable (defined as less pain or less physiological or psychological distress). This can sometimes become apparent when the patient displays extreme reluctance or inability to cope with a reduction in opioid dose.

Risk of overdose

There is a risk of overdose with rising doses of opioid(s), especially when opioids are used in conjunction with other medications that contribute to overdose risk (e.g. gabapentinoids, benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants). Importantly, the effects of overdose with oral, sublingual and transdermal prescription opioids differ from those of overdose with injected opioids such as heroin and fentanyl. The latter is characterised by the triad of pinpoint pupils, respiratory depression and unconsciousness.

In contrast, prescription opioid overdose (or toxicity) is more subacute in nature, with progressive sedation associated with a raised CO2 level and a degree of airway obstruction, commonly during sleep (mixed central and obstructive sleep hypoventilation). Clinicians can identify this phenomenon by asking patients, and particularly their partners or carers, about interrupted sleep, ‘unusual snoring’, sometimes louder than normal, excessive effort to breathe, or choking or spluttering sounds when sleeping. The presence of any of these signs should be taken as a potential marker of risk of opioid overdose (toxicity).

Aberrant behaviour

Aberrant behaviour that can be associated with prescription opioid use includes:

- attending multiple doctors or multiple pharmacies to access opioids

- misuse, or taking the opioid not as prescribed and not as authorised by the prescriber. Examples include stockpiling the opioid to use on a given occasion rather than taking as specified on the prescription, and use of the opioid for reasons other than pain, such as to manage stress or assist with sleep

- diversion, when the patient gives or sells their prescription opioid to another person.

Pathophysiology of opioid dependence and opioid use disorder

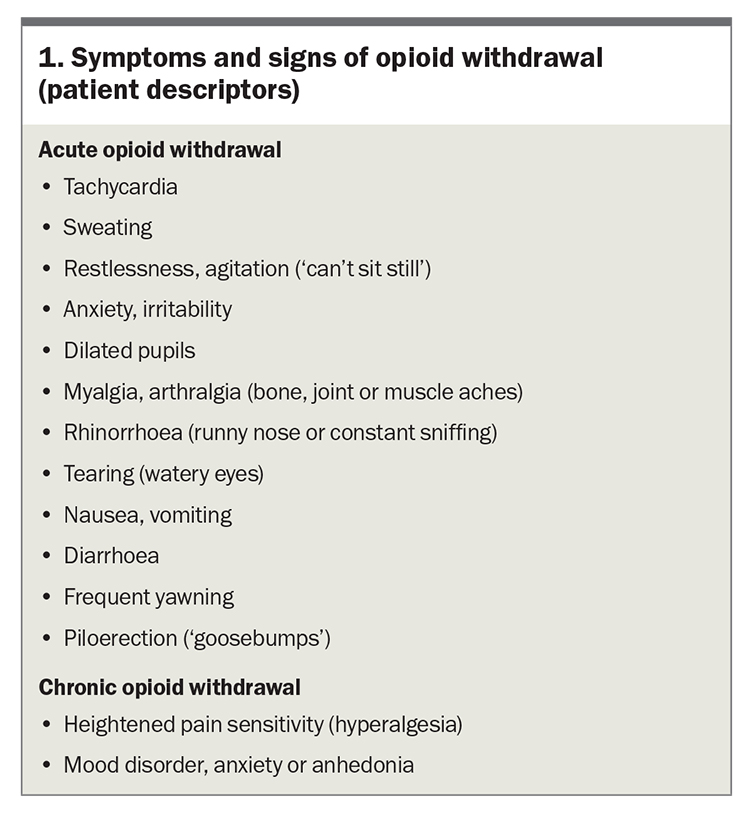

Prolonged administration of opioids results in neuroadaptation or opioid dependence. After neuroadaptation occurs, any sudden cessation or reduction in dose results in opioid withdrawal symptoms (Box 1). Patients sometimes do not realise these symptoms are a result of the opioid dose reduction. Withdrawal symptoms do not necessarily equate to opioid use disorder, but rather to neuroadaptation. It is important to explain to the patient that neuroadaptation is a normal physiological response and can be managed. Generally, it is not helpful to use the term ‘addicted to opioids’ as patients can often feel judged or stigmatised by this term. Rather, ‘dependence on opioids’ is a preferred terminology.

Behaviours that indicate opioid use disorder include aberrant use, including misuse of prescribed opioids or diversion of opioids, injecting behaviour and use of heroin in addition to, or in place of, prescription opioids.9 In these cases, opioid agonist treatment with buprenorphine or methadone is indicated, also termed opioid replacement treatment, opioid substitution treatment and medication-assisted treatment of opioid dependence (MATOD). This form of treatment requires application for a permit and training in how to prescribe these pharmacotherapies (available through the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners).10,11

Risk factors for chronic pain and prolonged prescription opioid use

Administration of opioids for a short period for acute pain (e.g. after a significant surgical procedure) is usually appropriate. The period of time that opioids are taken after the episode of acute pain should be kept to a minimum, to avoid the development of neuroadaptation. Opioid use for longer than 90 days is considered a ‘red flag’ that indicates increasing risk of prolonged opioid use.

Risk factors that have been implicated as increasing the risk of developing chronic pain and prolonged opioid use include:

- excessive pain (disproportionate to the level of pain typically expected after a given procedure or with a given condition)12,13

- history of adverse childhood experiences

- past substance dependence (e.g. alcohol, prescription medications, illicit substances)

- mental health problems (e.g. anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder)

- adverse psychosocial factors (e.g. interpersonal violence or family violence, unstable financial circumstances or unstable accommodation).14

There are similarities in the risk factors for persistent pain and for opioid dependence. Consequently, this cohort has the potential to develop a dual diagnosis of persistent pain and opioid dependence, or even a triple diagnosis that includes comorbid mental health diagnoses such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder or personality disorders.

Assessment of patients with prolonged prescription opioid use

Assessment of a patient with prolonged use of prescription opioids requires a holistic history. This includes an understanding of the event that led to the opioids being commenced (e.g. accident, injury, surgery or other) and the current dose.

The current dose allows the oral morphine equivalent daily dose (OMEDD) to be calculated. An OMEDD calculator app is available from the Faculty of Pain Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (www.opioidcalculator.com.au).15 This calculator estimates whether the patient’s daily dose of opioid is in the ‘green’, ‘orange’ or ‘red’ zone, as a measure of risk of opioid-related harm, specifically the risk of overdose, including death.

Daily opioid doses greater than 100 mg of morphine or equivalent significantly increase the risk of adverse effects, including overdose. People with an OMEDD greater than 50 mg and a high total dose over the preceding six months were found to be at higher risk compared with those taking lower dosages.16 These doses should prompt review to reduce risk, through decreasing the dose and reducing or ceasing concomitant medications that contribute to overdose.

Management of patients with prolonged prescription opioid use

Discussion of opioid risks and complications

Open and ongoing discussion with the patient about the potential risks of prolonged opioid use is required. This includes:

- describing the risk of overdose. This can be assessed in part from the OMEDD and consideration of coexisting risk factors such as sleep apnoea and coprescribed sedatives or by asking carers if they have noticed symptoms during sleep (as described above). Take-home naloxone nasal spray should be provided for the patient to have on hand should overdose occur (see below).17

- outlining the complications of long-term use of prescription opioids (Box 2)

- when there is polypharmacy, discussing rationalisation of the medication regimen with the patient, especially when they are taking multiple opioids or opioids in conjunction with other sedative medications.

Opioid tapering or rotation

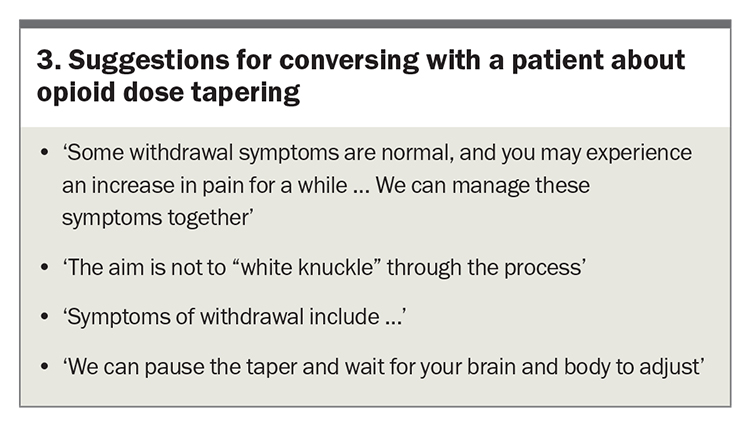

An opioid tapering program with dose monitoring is commonly advised.8,18 The choice of a fast or slow taper at both the current dose and on withdrawal should be discussed with the patient. This choice will be influenced by the level of risk based on the OMEDD, duration of opioid use, presence of polypharmacy and comorbidities such as respiratory disease. An important aspect of this discussion is to enquire about the patient’s concerns about the proposed management plan and to allay any anxieties. Some suggestions for engaging in this conversation are shown in Box 3.

However, in some patients, rotation to prescription opioids with a better safety profile may be a more acceptable and pragmatic approach. Where opioids are indicated (for nociceptive pain), atypical opioids with dual modes of action and relatively weaker action at the mu opioid receptor for analgesia equivalence may be preferable. These include buprenorphine (low-dose transdermal or sublingual), tapentadol and tramadol.

Clonidine, an alpha-2 receptor agonist commonly used as an atypical antihypertensive, may be considered to assist in opioid dose reduction or rotation (off-label use). Clonidine has direct analgesic, anxiolytic and muscle relaxant properties via neuromodulation and reduces opioid-induced hyperalgesia and opioid withdrawal effects. The recommended dose for this purpose is 50 to 100 mcg clonidine three times daily, regularly or as required for symptom control.

Importance of language used

The language used when discussing prescription opioid problems with patients is a key consideration for successful interaction.

The term ‘addict’ should never be used. If the patient brings it up, as often occurs (e.g. ‘I’m not an addict!’), then reframing the dialogue to a discussion about how the brain and the body have adapted, changed or become accustomed to, or dependent on, the opioids can be helpful.

Address the ‘de-conditioning’. Many patients have become unfit over time or reduced their mobility. Hence, it is important to discuss the value of physical therapies and exercise to assist the approach to addressing the prescription opioid regimen.

Reassure the patient ‘We won’t stop things suddenly’. This is often an underlying concern that the patient may, or may not, make known to the prescriber. Stopping an opioid suddenly will bring on withdrawal symptoms and signs, which is to be avoided where possible. However, some individuals may experience discomfort as the dose reduces. Research indicates that patients will engage in an adequately supported voluntary outpatient dose taper regimen.19

Other aspects of management

Other aspects of management of people with long-term prescription opioid use include:

- comprehensive assessment of mental health, as high-dose prescription opioids are more likely to be associated with anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder20,21

- targeting an ultimate goal of restoring or maximising function, which may include involving a physiotherapist or other health professionals to address biological, psychological and social issues, rather than a focus on medication as the best approach to treatment.

Risk mitigation strategies

Strategies to reduce the risk of developing negative consequences of prolonged prescription opioid use include the following.

Prevention

Preventing prolonged use of prescription opioids without demonstrated sustained benefit for noncancer and cancer-survivor pain is key. Setting an expectation that acute pain is expected and will resolve, along with the requirement for opioids, is important. Consistent communication and messages from the primary care physician and other doctors involved in care of the patient is important.

The duration of prescription opioid use should be kept to a minimum to avoid neuroadaptation. Immediate-release formulations are recommended in preference to slow-release formulations as similar benefits but lower rates of harm have been identified; however, in some situations extended-release formulations may enable the patient to function better.22 The use of adjuvant medications (including anti-inflammatories, clonidine and tricyclic antidepressants) reduces the potential for opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

Multimodal analgesia

Multimodal analgesia, both pharmacological (with nonopioids such as NSAIDs or paracetamol) and nonpharmacological (e.g. physiotherapy or hydrotherapy), is opioid-sparing and assists holistic recovery. Sometimes, the input of a psychologist is helpful if the patient is experiencing difficulty adjusting to their situation or if there are unresolved mental health issues.

Single prescriber

Having a single prescriber is the safest approach to avoid duplication of prescriptions or polypharmacy. Real-time prescription monitoring systems, which have been introduced in several Australian states and territories, are helpful in identifying patients who are accessing medications from more than one prescriber. Where this is identified, a conversation with the patient is needed about the importance of their safety and preventing adverse outcomes and ascertaining who will be their sole prescriber.

Staged supply

Consider weekly or several times weekly pick up from the pharmacy for patients deemed to be at higher risk of overdose or misuse of opioids. Risk factors include a past history of overdose (intentional or unintentional), tendency to impulsivity, high OMEDD and heavy consumption of alcohol. Some health professionals document a written opioid plan and provide a copy to the patient, primary care physician, pharmacist and other health professionals involved in the care of the patient to help maintain patients on a specific dose or to aid in slowly reducing the dose if that is part of the agreement.

Take-home naloxone

All patients on a high OMEDD (more than 100 mg daily) or with coexisting risk factors for toxicity (e.g. OMEDD more than 50 mg daily with coprescribed sedatives) should be provided with take-home naloxone in the form of a nasal spray. Their carers or family members should be instructed on when and how to use this.23

Specialist support

Referral to a pain medicine or addiction medicine specialist, especially in a shared-care arrangement, can be useful in helping the patient understand the reasons for concern about the prescription opioids they are taking. Some patients with persistent pain require ongoing small or moderate doses of opioids. In this group, the continued use of opioids can be justified or reflected in the patient’s function and capacity.

Opioid agonist therapy when indicated

When an individual displays evidence of opioid use disorder, a pain or addiction specialist can assist with discussion of medication-assisted treatment for this disorder or provide the individual with a second opinion if they are resistant to advice about this.

In selected cases where pain control remains poor and the risk (dose) is high, rotation to high-dose buprenorphine in the form of sublingual or long-acting injectable preparations should also be considered.24 Note that these pharmacotherapies are TGA-approved for ‘treatment of opioid dependence’ and not for pain management. Rules and regulations pertaining to prescribing these pharmacotherapies vary between jurisdictions, including the training requirements before prescription. Therefore, it is important to check the relevant medicolegal requirements. A second opinion and support should be sought to limit the risk of distress associated with rotation from high-dose prescription opioids to a high-dose buprenorphine strategy.

Conclusion

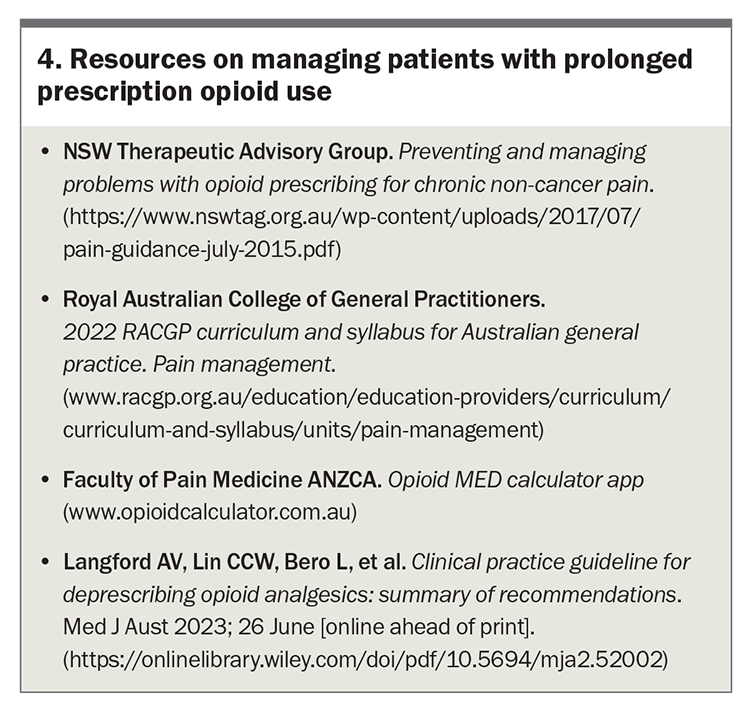

All health professionals have a role in reducing the risks associated with long-term prescription opioid use in the community. Resources to help GPs manage patients with long-term prescription opioid use are listed in Box 4. Whatever the context, whether on patient discharge from hospital or in the community, all prescribers must ensure responsible practice in their approach to opioid prescribing. Educating patients that the goal is to achieve optimal health, which includes reducing but not necessarily eradicating pain, via a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological methods, is the most effective way of achieving the best outcomes for patients. PMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Associate Professor Bonomo has received honoraria from Indivior and Camurus, manufacturers of high-dose buprenorphine and long-acting injectable buprenorphine, respectively. Associate Professor Hogg has received honoraria for lecture presentations on cancer pain from Mundipharma.

References

1. Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain 2001; 89: 127-134.

2. Scholten W, Christensen AE, Olesen AE, Drewes AM. Analyzing and benchmarking global consumption statistics for opioid analgesics 2015: inequality continues to increase. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2020; 34: 1-2.

3. Chrzanowska A, Man N, Sutherland R, Degenhardt L, Peacock A. Trends in overdose and other drug-induced deaths in Australia, 1997-2020. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney; last updated 2022. Available online at: https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/resource-analytics/trends-drug-induced-deaths-australia-1997-2020 (accessed June 2023).

4. NSW Therapeutic Advisory Group. Preventing and managing problems with opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain. Sydney: NSW TAG; 2015. Available online at: https://www.nswtag.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/pain-guidance-july-2015.pdf (accessed June 2023).

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA 2016; 315: 1624-1645.

6. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. Prescribing opioids for pain – the new CDC clinical practice guideline. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 2011-2013.

7. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain – United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep 2022; 71: 1-95.

8. Langford AV, Lin CCW, Bero L, et al. Clinical practice guideline for deprescribing opioid analgesics: summary of recommendations. Med J Aust 2023; 26 June [online ahead of print]. Available online at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.5694/mja2.52002 (accessed June 2023).

9. Passik SD, Messina J, Golsorkhi A, Xie F. Aberrant drug-related behavior observed during clinical studies involving patients taking chronic opioid therapy for persistent pain and fentanyl buccal tablet for breakthrough pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011; 41: 116-125.

10. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, Therapeutics Goods Administration. Prescription opioids: what changes are being made and why. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; last updated 2021. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/products/medicines/prescription-medicines/prescription-opioids-hub/prescription-opioids-what-changes-are-being-made-and-why (accessed June 2023).

11. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Alcohol and other drugs. GP education resource library. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/alcohol-and-other-drugs (accessed June 2023).

12. Khan RS, Ahmed K, Blakeway E, et al. Catastrophizing: a predictive factor for postoperative pain. Am J Surg 2011; 201: 122-131.

13. Theunissen M, Peters ML, Bruce J, Gramke HF, Marcus MA. Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain 2012; 28: 819-841.

14. Scott KM, Von Korff M, Angermeyer MC, et al. Association of childhood adversities and early-onset mental disorders with adult-onset chronic physical conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 838-844.

15. Faculty of Pain Medicine, ANZCA. Opioid calculator. Available online at: http://www.opioidcalculator.com.au/ (accessed June 2023).

16. Liang Y, Turner BJ. Assessing risk for drug overdose in a national cohort: role for both daily and total opioid dose? J Pain 2015; 16: 318-325.

17. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Take home naloxone program. Last updated 2023. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/take-home-naloxone-program (accessed June 2023).

18. NPS Medicinewise. 5 steps to tapering opioids for patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Medicinewise News 2020; 1 January. Available online at: https://www.nps.org.au/news/5-steps-to-tapering-opioids (accessed June 2023).

19. Darnall BD, Ziadni MS, Stieg RL, Mackey IG, Kao MC, Flood P. Patient-centered prescription opioid tapering in community outpatients with chronic pain. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178: 707-708.

20. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain 2010; 26: 1-8.

21. Feingold D, Brill S, Goor-Aryeh I, Delayahu Y, Lev-Ran S. Depression and anxiety among chronic pain patients receiving prescription opioids and medical marijuana. J Affect Disord 2017; 218: 1-7.

22. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Faculty of Pain Medicine. PS41(G) Position statement on acute pain management 2022. Available online at: https://www.anzca.edu.au/getattachment/558316c5-ea93-457c-b51f-d57556b0ffa7/PS41-Guideline-on-acute-pain-management (accessed June 2023).

23. NSW Ministry of Health. Opioid overdose response. Consumer information sheet: Nyxoid. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2019. Available online at: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/aod/programs/Factsheets/naloxone-factsheet-nyxoid.PDF (accessed June 2023).

24. Chong J, Frei M, Lubman DI. Managing long-term high-dose prescription opioids in patients with non-cancer pain: ‘the potential role of sublingual buprenorphine’. Aust J Gen Pract 2020; 49: 339-343.