A middle-aged woman with a stiff painful shoulder

This case highlights the importance of using appropriate imaging to exclude more serious problems when diagnosing the cause of shoulder pain. As it may take some time for the pain and stiffness of adhesive capsulitis to resolve, treatment needs to include supportive management with psychological support and adequate analgesia.

- All patients presenting with clinical features consistent with adhesive capsulitis should have imaging with an x-ray, at a minimum.

- For patients older than 60 years or younger than 40 years who present with a stiff painful shoulder, there should be a low threshold for further imaging with an MRI scan.

- Patients with diabetes respond less well to all treatment options.

- A glenohumeral joint injection with corticosteroids, with or without hydrodilatation, usually reduces symptoms within a few weeks, although some patients take longer to improve and may require further injections.

- Surgery is rarely necessary for adhesive capsulitis.

Case scenario

Tania, a 53-year-old perimenopausal woman, presented to her GP with left shoulder pain. She had been walking her dog on a lead six weeks previously, when it had pulled her shoulder. She had minor discomfort at the time but noticed gradually increasing pain over the next few weeks. This was a minor problem at rest but became more severe with activities, particularly those involving stretching. Tania noticed that she had some restriction in function, with difficulty lifting her arm fully overhead and doing up her bra. There was some pain at night. She had no specific treatment for the shoulder, apart from taking paracetamol for the pain, and no significant medical history. Her GP ordered an ultrasound and referred her to an orthopaedic specialist.

The ultrasound showed no damage to the tendons but mild impingement on abduction. On examination, there was some distinct restriction in glenohumeral movement in all directions. External rotation and passive abduction were limited by 30 degrees. This loss of passive range of motion is an important clinical sign of adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder). Active elevation was above shoulder level but restricted to 110 degrees. She experienced pain at extremes of movement. There was good power of the shoulder, with no weakness on testing the rotator cuff muscles. Acromioclavicular compression test results were negative.

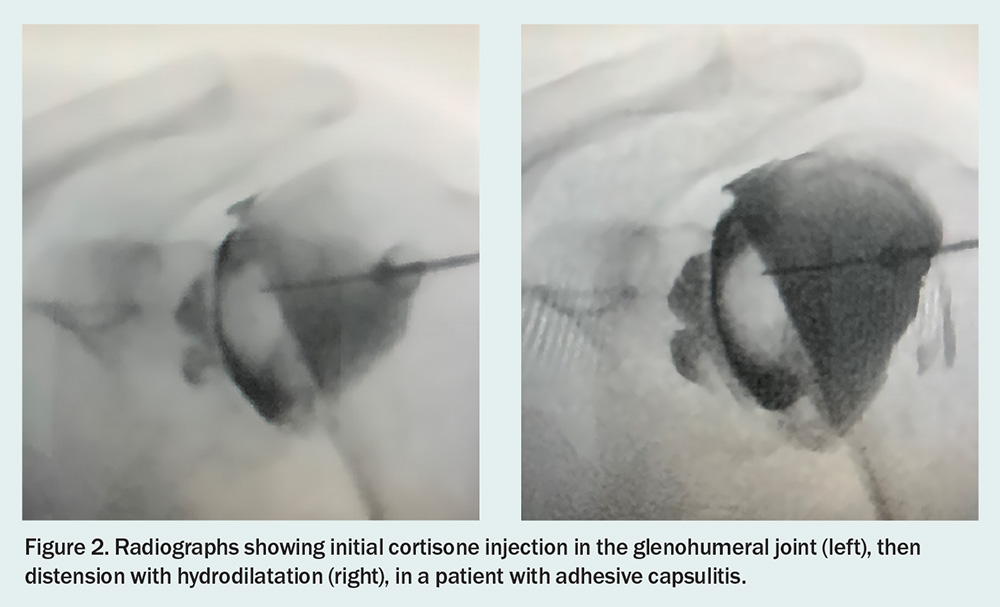

In a woman aged 53 years with a stiff painful shoulder, adhesive capsulitis was the most likely diagnosis, but an x-ray was needed to exclude other possible problems. Tania’s x-ray showed no abnormality, with normal bony structures and no sign of arthritis in the glenohumeral joint. The diagnosis was therefore considered to be adhesive capsulitis. The many possible management options were discussed with her. It was decided that she would have a hydrodilatation – a procedure where the glenohumeral joint is injected with cortisone, then saline is injected under pressure to distend the capsule.

After the hydrodilatation was performed, she began a simple home stretching program, avoiding any movements that caused pain. When she was reviewed six weeks later, her pain had considerably reduced and range of motion had improved, with 15 degrees more movement in all directions than previously, but was still restricted to some extent. She reported that this did not overly trouble her, as most of her pain had resolved.

Tania was followed up after another six weeks. At this stage, there had been further improvement in her range of motion, and she no longer had any significant pain. She began a physiotherapy program, mainly to improve strength around the shoulder. Ultimately, her shoulder returned to normal.

Commentary

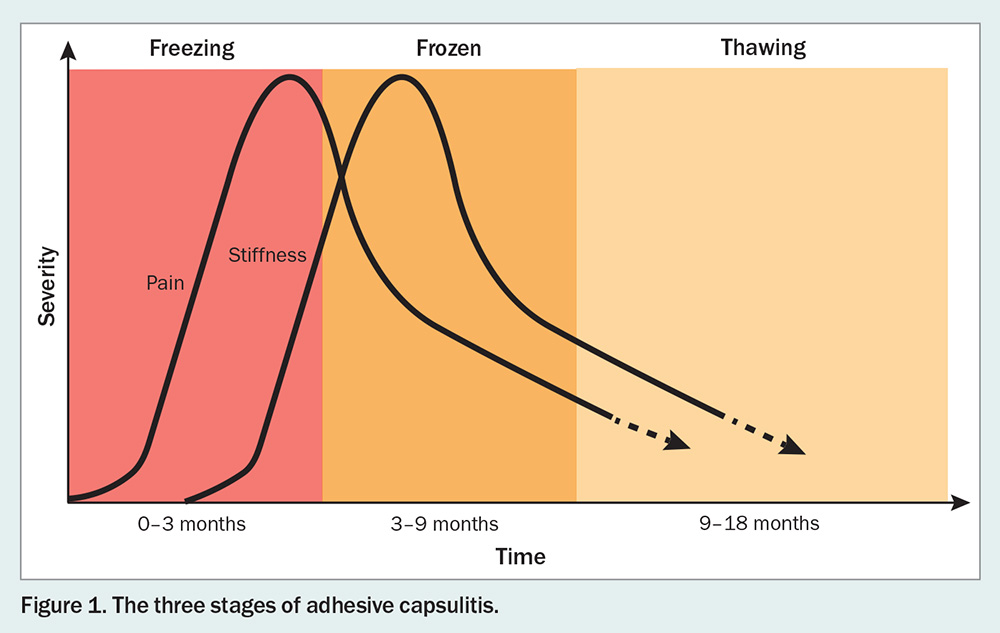

Adhesive capsulitis, or frozen shoulder, is an idiopathic condition causing pain and stiffness in the shoulder, which can completely resolve over time and can be improved with appropriate treatment. The underlying disease process is still not fully understood.1 However, studies have shown there is an underlying low-grade inflammatory process that leads to a proliferation of fibroblasts, causing a stiffer and thicker capsule.1 The condition is described as having three phases, with a painful freezing stage followed by a stiff frozen stage, then a thawing or recovery stage (Figure 1).2 Adhesive capsulitis is a common condition, with a prevalence of between 2 and 5%, and up to 13% in patients with diabetes.3 It is more common in women and rarely occurs under the age of about 35 to 40 years, peaking around the age of 56 years. Patients with diabetes respond less well to all management options.4 The pain from the condition is usually more concerning to the patient than the loss of range of motion.

Although it is described as a self-limiting condition, the time scale for recovery and response to various treatments is extremely variable.5 In some cases, full range of movement is never recovered, particularly in patients with diabetes.2

Diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis

There is no investigation of a shoulder with adhesive capsulitis that can definitively confirm the diagnosis, so it is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion. Patients with a possible diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis present with painful restriction in glenohumeral movement and show no abnormality on imaging.6,7 However, coexisting abnormalities may be seen on x-ray and ultrasound, if performed. MRI can show changes related to adhesive capsulitis, but these are not definitive. There are several other diseases, such as an inflammatory arthropathy or pseudogout in the joint, that can present with features similar to those of adhesive capsulitis. It is extremely important to exclude other possible diagnoses with imaging, as a tumour in or around the shoulder can also present with restricted motion and pain.8 At a minimum, an x-ray is necessary, particularly to exclude any underlying osteoarthritis or tumour. An ultrasound is not adequate to exclude other significant abnormalities that can cause painful shoulder stiffness. Ultrasound also often reports the presence of subacromial bursitis and impingement; this can lead to treatment with subacromial injection, which provides minimal benefit and distracts from the real problem.

Therefore, if a patient in an at-risk group for adhesive capsulitis, which is predominantly middle-aged women, has an examination that fits the diagnosis, as well as a normal x-ray, this is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis and organise appropriate treatment.

The more concerning group is older patients, as other causes of shoulder pain are more common in this group. Therefore, for patients aged over 60 years who present with a stiff painful shoulder, there should be a low threshold for further imaging, particularly with an MRI scan. Patients younger than 40 years should also be considered for an MRI, as adhesive capsulitis is rare in this group, and it is important to exclude other more serious problems, such as a tumour, pigmented villonodular synovitis or an arthropathy. An MRI scan can distinguish between adhesive capsulitis and an arthropathy, particularly an inflammatory arthropathy with only minor chondral damage. Typically, an MRI scan in a patient with adhesive capsulitis shows contracture of the inferior recess, hyperintensity of the capsule and axillary capsule, and coracohumeral ligament thickness.8 Features on an MRI scan are often not completely diagnostic for adhesive capsulitis but can eliminate other causes, particularly an inflammatory arthropathy, which has different MRI features than adhesive capsulitis.9,10

Treatment options

Many treatments for adhesive capsulitis have been described, with the most common being supervised neglect, oral corticosteroids, suprascapular nerve block, and corticosteroid injection in the joint, which can be combined with hydrodilatation. Surgical options, which include manipulation and arthroscopic capsular release, are rarely necessary. Some studies have shown no advantage of surgical treatment over nonoperative management.5

A common form of management for adhesive capsulitis is an imaging-assisted intra-articular cortisone injection, which can be combined with saline distension of the joint, known as hydrodilatation or hydrodistension (Figure 2). A cortisone injection in the glenohumeral joint, with or without hydrodilatation, has demonstrated a beneficial effect in many studies.11-15 Although there is mixed evidence in the literature, a meta-analysis comparing conservative forms of management of frozen shoulder recommended hydrodilatation as the conservative treatment of choice.16 If, about three months after the first injection, the patient still has residual troublesome pain and stiffness, a second and possibly even a later third injection can be considered, to achieve resolution of the adhesive capsulitis. One study found that a second injection is not routinely required if patients have a good response to the initial hydrodilatation, but further improvement could be gained with a second injection if there were residual symptoms.17 A recent study found that there was further improvement with a second injection after six weeks; however, there was no control group in this study.18

Several studies have shown benefit from using suprascapular nerve block in the management of adhesive capsulitis, particularly when combined with intra-articular injection or hydrodilatation. Further studies are needed to determine the role of suprascapular nerve block in treating frozen shoulder.19

Physiotherapy is often used in the management of adhesive capsulitis. Although there are few studies comparing physiotherapy with supervised neglect, some studies have reported superior long-term outcomes with supervised neglect.20

Supportive management

It needs to be explained to patients with adhesive capsulitis that, although it is a disabling and at times distressing condition, it is not ultimately serious and almost all cases resolve.2 However, they do need to understand that the resolution process is often extremely prolonged, taking many months. Patients with diabetes require specific counselling about a possible longer duration of symptoms and the potential need for repeat treatment, such as with a second intra-articular cortisone injection.

Some studies have shown that physiotherapy offers only a minor benefit for patients with adhesive capsulitis, but it can be useful in the late recovery period to improve strength.20

The patient will need psychological support during this time, as well as adequate analgesia, particularly to control any night pain. In most cases, regular doses of paracetamol are all that is needed for the pain. Anti-inflammatory drugs do not appear to be beneficial.21 The use of narcotics should be avoided, as they would need to be continued for a prolonged period if started.

Summary

Adhesive capsulitis is a poorly understood condition which, in most cases, resolves with conservative management.2 There are minimal long-term sequelae, apart from a permanent slight loss of motion in some cases. Patients with diabetes respond less well to all treatment options and, in some cases, the adhesive capsulitis does not completely resolve.

The mainstay treatment for adhesive capsulitis is an intra-articular cortisone injection, which can be combined with hydrodilatation using saline. In most cases, this will settle the pain to an adequate extent within a few months, although the pain and stiffness will take longer to settle in a significant number of patients. However, very few patients will have persistent symptoms. PMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Kraal T, Lübbers J, van den Bekerom MPJ, et al. The puzzling pathophysiology of frozen shoulders – a scoping review. J Exp Orthop 2020; 7: 91.

2. Wong CK, Levine WN, Deo K, et al. Natural history of frozen shoulder: fact or fiction? A systematic review. Physiotherapy 2017; 103: 40-47.

3. Zreik NH, Malik RA, Charalambous CP. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder and diabetes: a meta-analysis of prevalence. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2016; 6: 26-34.

4. Sharma SP, Moe-Nilssen R, Kvåle A, Bærheim A. Predicting outcome in frozen shoulder (shoulder capsulitis) in presence of comorbidity as measured with subjective health complaints and neuroticism. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017; 18: 380.

5. Rangan A, Goodchild L, Gibson J, et al. Frozen shoulder. Shoulder Elbow 2015; 7: 299-307.

6. Codman EA. The shoulder: rupture of the supraspinatus tendon and other lesions in or about the subacromial bursa. Boston: Thomas Todd; 1934.

7. Zuckerman JD, Rokito A. Frozen shoulder: a consensus definition. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 322-325.

8. Tamai K, Hamada J, Nagase Y, et al. Can magnetic resonance imaging distinguish clinical stages of frozen shoulder? A state-of-the-art review. JSES Rev Rep Tech 2024; 4: 365-370.

9. Prakash M, Sharma M, Sinha A, Choudhury SR, Chouhan DK. MRI in shoulder arthropathies: a short review. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2024; 50: 102384.

10. Suh CH, Yun SJ, Jin W, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging features for diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 566-577.

11. Buchbinder R, Green S, Forbes A, Hall S, Lawler G. Arthrographic joint distension with saline and steroid improves function and reduces pain in patients with painful stiff shoulder: results of a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 302-309.

12. Bell S, Coghlan J, Richardson M. Hydrodilatation in the management of shoulder capsulitis. Australas Radiol 2003; 47: 247-251.

13. Sharma SP, Bærheim A, Moe-Nilssen R, Kvåle A. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder, treatment with corticosteroid, corticosteroid with distension or treatment-as-usual; a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016; 17: 232.

14. Yoon JP, Chung SW, Kim JE, et al. Intra-articular injection, subacromial injection, and hydrodilatation for primary frozen shoulder: a randomized clinical trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016; 25: 376-383.

15. Rasool A, Raza Khan K, Gillani H, Rashid M, Umair M, Israr H. Comparison of intra-articular steroid injection versus hydrodilatation with saline and corticosteroid for the treatment of refractory adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Professional Med J 2023; 30: 971-976.

16. Lädermann A, Piotton S, Abrassart S, Mazzolari A, Ibrahim M, Stirling P. Hydrodilatation with corticosteroids is the most effective conservative management for frozen shoulder. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2021; 29: 2553-2563.

17. Trehan RK, Patel S, Hill AM, Curtis MJ, Connell DA. Is it worthwhile to offer repeat hydrodilatation for frozen shoulder after 6 weeks? Int J Clin Pract 2010; 64: 356-359.

18. Wang W-H, Chen P, Lu LY, Yang C-P, Chiu JC-H. The different effects of 2 consecutive glenohumeral injections of corticosteroids on pain reduction and range-of-motion improvement in frozen-phase frozen shoulder. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2024 Oct 9; 101025 [Online ahead of print].

19. Jump CM, Waghmare A, Mati W, Malik RA, Charalambous CP. The impact of suprascapular nerve interventions in patients with frozen shoulder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JBJS Rev 2021; 9(12). doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.21.00042. Erratum in: JBJS Rev 2022; 10(3). doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.ER.21.00042.

20. Maruli Tua Lubis A, Riyan Hartanto B, Kholinne E, Deviandri R. Conservative treatment for idiopathic frozen shoulder: is supervised neglect the answer? A systematic review. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2022; 56: 340-346.

21. Berner JE, Nicolaides M, Ali S, et al. Pharmacological interventions for early-stage frozen shoulder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024 Mar 27; keae176 [Online ahead of print].