Fibromyalgia – an update on management

Fibromyalgia is a common chronic pain disorder that presents challenges in understanding its pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Multidisciplinary strategies that include psychological approaches, regular gentle movement and medications targeting pathophysiological processes are the most effective for management.

- Fibromyalgia is a common nociplastic pain condition with varying clinical features.

- The pathophysiology of fibromyalgia involves multiple changes in the central sensory processing system linked to the activation of a central stress response.

- A multidisciplinary approach to management remains the most effective.

- Psychological strategies and regular gentle movement are essential to manage the symptoms of fibromyalgia.

- Medications targeting the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are helpful.

Fibromyalgia is a common, chronic disorder with features of nociplastic pain, fatigue, sleep problems, cognitive disturbance and increased central sensitivity. In patients with fibromyalgia, pathophysiological changes in the central and peripheral nervous systems link to altered sensory processing. This review focuses on the management of fibromyalgia following a brief overview of its pathophysiology and diagnosis.

Pathophysiology

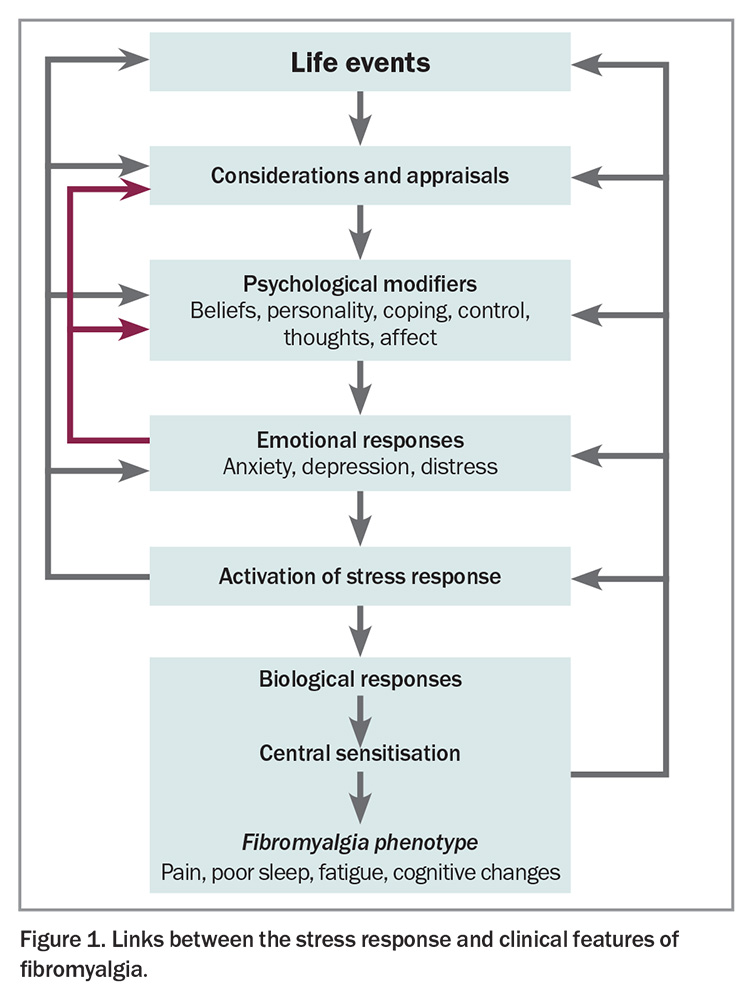

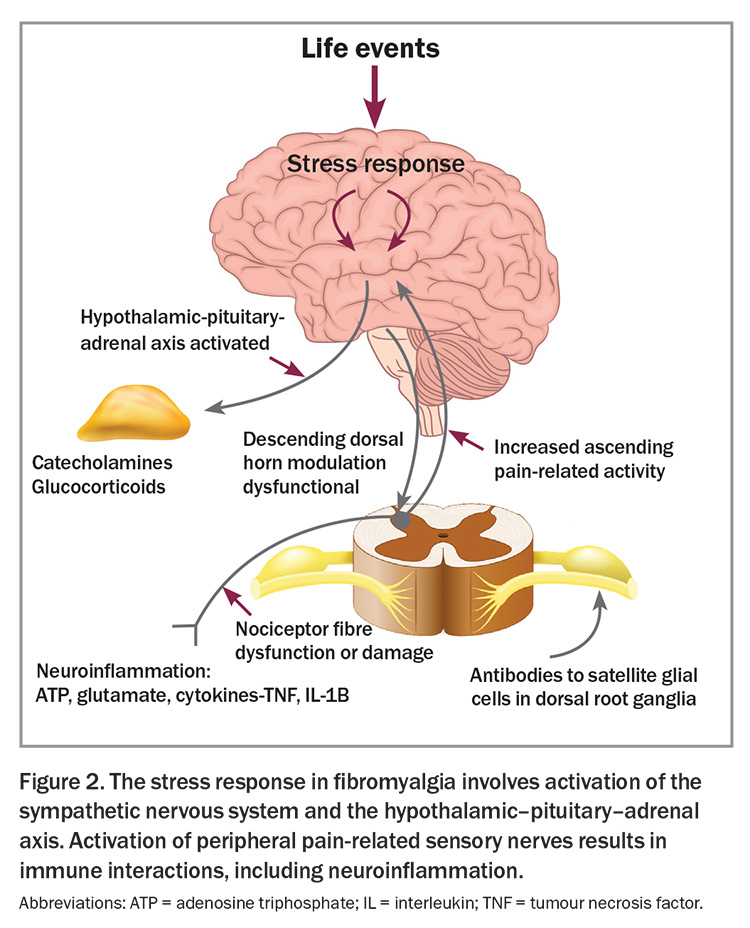

Although the precise mechanisms leading to the clinical features of fibromyalgia are not fully established, the condition is strongly associated with stress, be it psychological or physiological.1 Activation of the stress response is associated with increased sensitivity in various sensory systems including the pain-related neural systems (Figure 1). Several changes in neural networks and changes in descending neural control of afferent sensory information have been identified in the spinal cords of patients with fibromyalgia.2 In fibromyalgia, central neuroinflammation is marked by elevated levels of proinflammatory substances, such as neuropeptides substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide, as well as glutamate, cytokines and chemokines, among others.1 The sympathetic nervous system is activated, contributing to the pathophysiology and symptoms. Changes in spinal cord and brain function dominate the pathophysiology and are potentially responsive to pharmacological modulation.

There are also downstream effects beyond the spinal cord, associated with neuroinflammatory processes in nociceptive nerves, which contribute to the increased sensitivity of peripheral neural systems, causing soft tissue tenderness, muscle tightness and dermatographia (Figure 2).

Pain definitions

In the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision, fibromyalgia is identified as primary pain, that is, pain not secondary to another disease process.3 The pain mechanism of fibromyalgia is an example of nociplastic pain, a term used to identify sensitisation of nociceptive and other pain-related neural mechanisms.4,5 Sensitisation, in turn, is associated with increased responsiveness of neural activity following a given stimulus; in fibromyalgia, this could be typical low-level sensory input, such as touch or movement, which result in widespread areas of pain. Additionally, there is increased responsiveness to other normal sensory input, such as light and noise, in fibromyalgia. These observations, and others, highlight the presence of central sensitisation as a key feature of fibromyalgia.2

Diagnosis of fibromyalgia

There is no specific diagnostic test for fibromyalgia. The diagnosis remains clinical. As such, there are several clinically based criteria that have been used to define the diagnosis, and these are built on the identification of common presenting clinical features. These include widespread pain and widespread abnormal tenderness, together with high levels of poor-quality sleep, fatigue and cognitive dysfunction.

Criteria

A number of criteria have been promulgated by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) over the last few decades. The first widely accepted classification criteria were the ACR 1990 criteria.6 These criteria are based on the presence of a high number of tender points. These are predesignated sites in the body that are naturally more tender than surrounding sites and result in significantly higher levels of pain on application of a prespecified manual stimulus (e.g. light pressure enough to blanch the examiner’s thumb or index finger). This is termed allodynia. Widespread pain and tenderness are key features of fibromyalgia.

Later, the ACR 2016 criteria were presented as simplified and purely patient self-reported criteria, with a requirement of the presence of widespread pain (in four quadrants and the spine), together with high ratings of poor sleep, fatigue and poor cognition, and a small contribution from depression, abdominal pain and headache.7 The symptoms are required to be present for three months, although it is recognised that fibromyalgia can occur over days to weeks after certain triggers (discussed further below). These criteria have a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 90%, measured against the original 1990 criteria. A body map to identify widespread pain, included in these criteria, is helpful for diagnosis.8

Mimics

Importantly, for a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, there must be no other explanation for the symptoms and signs that are present. Hence, a careful clinical history and examination are required, together with targeted investigations for possible relevant mimicking disorders. It is usual for investigations to include a full blood examination, measurements of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels, liver function tests, renal function tests, thyroid function tests and, if indicated, measurement of vitamin D levels, iron studies and screening serological tests (e.g. antinuclear antibody, anticitrullinated peptide antibody, rheumatoid factor). Notably, levels of inflammatory markers will be normal; any deviations may reflect the activity of comorbid conditions. Other investigations, such as imaging, might be included depending on the clinical presentation.

Fibromyalgia is not a diagnosis of exclusion nor an exclusive diagnosis. This is important, as it means that fibromyalgia is an independent diagnosis based on accepted clinical criteria; overzealous testing for other mimicking conditions is not required before establishing the diagnosis. Additionally, if a diagnosis of fibromyalgia has been established, then that does not rule out other conditions as a cause of some of the musculoskeletal symptoms. This is a common scenario.

Comorbidities

The current criteria indicate a prevalence of fibromyalgia of 2 to 5% in most communities. Using these criteria, the female-to-male ratio is closer to 2:1 than previous estimates of up to 6:1. The frequency of fibromyalgia increases significantly where patients have one of several chronic diseases, such as inflammatory or degenerative arthritis, chronic heart failure, chronic liver or kidney disease, among others. In this setting, the prevalence of fibromyalgia increases by 10-fold or more.

Hypermobility is common in people with fibromyalgia, but this does not necessarily imply the presence of an additional diagnosis of genetically associated hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Many patients with fibromyalgia are labelled as having chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis, or with names associated with the putative trigger for the symptoms (e.g. railway spine, shell shock, neurasthenia and long-COVID).

Triggers

Fibromyalgia may develop slowly over time but is commonly triggered by a specific event, which might include one causing emotional distress, trauma or viral infection (including COVID-19).

Psychological factors

Emotional distress is common in fibromyalgia. Depression is a common comorbidity but is not shown to be a cause of fibromyalgia by itself. Patients with anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder have increased rates of fibromyalgia.9

Spectrum and trajectory

The symptoms of fibromyalgia exist on a spectrum.10 Many people in the community have low levels of symptoms characteristic of fibromyalgia (poor sleep, fatigue, muscle aches, soft-tissue tenderness or cognitive dysfunction [often termed ‘fibro fog’]), but these do not fulfil a criteria-based diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Many patients who are diagnosed with fibromyalgia have key symptoms that fluctuate significantly in severity over time, experiencing remission and flare-ups, often modulated by stress.

Management

Principles

Fibromyalgia management is most effective when it is multifaceted, reflecting the diverse pathophysiological changes occurring in the central nervous system. Just as these changes do not contribute uniformly to the clinical profile in all people with fibromyalgia, management strategies also differ in their effectiveness between patients.

The multidisciplinary approach to management, including psychological strategies, physical movement practice and medications, remains the most effective way to impact the broad spectrum of symptoms. Nonpharmacological strategies are often the most helpful in the long term, if engagement and adherence are successful.

It is essential to gain an appropriate level of understanding of the patient’s psychosocial situation, clinical profile, previously used treatments and any barriers to therapies. It is also important to recognise that different management approaches may not always be available, manageable, tolerable, affordable or effective for patients. Attempting to weave together an effective and sustainable multidisciplinary program can sometimes take time and may need a pragmatic approach for both the clinician and patient.

Education

Early, effective and appropriate education provided to patients and their supporters is one of the most powerful therapeutic interventions available. It can provide understanding, offer validation of the wide spectrum of symptoms and help set expectations.11 Education must encompass:

- the concept of central sensitivity as a continuum with complex biopsychosocial aggravating and ameliorating influences

- nociplastic pain not being indicative of peripheral tissue damage

- the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to management.5

Education regarding the condition and its management can pave the way for active engagement by patients in their own management program and the improvement in outcomes that accompanies this boost in personal agency and sense of control.11,12

Psychological strategies

Psychological strategies have long been found to have significant benefits in the management of fibromyalgia.13,14 From the early recognition that poor sleep and high stress levels have a profound influence on the overall fibromyalgia clinical experience, these have been effective targets of influence in management programs. Regular, active practice of simple techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, focused breathing or guided imagery can be facilitated by group sessions, online information and mobile phone applications.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is the most studied principal modality of formal psychological therapy in patients with fibromyalgia, with robust findings of improved pain, fatigue, quality of life measures (such as health-related quality of life) and disability.15 The modulation of pain and the affective experience of pain by cognitive therapies is associated with altered functioning of brain regions in an extensive network including non-nociceptive regions seen on functional MRI.16 Accessing therapists for CBT and other pain management psychology can be difficult for some patients because of the scarcity of available practitioners, geography or finances. Interactive programs and online modules can offer convenient and effective alternative ways of accessing elements of CBT.17,18 Other than CBT, psychologists may use other approaches such as those directed to past trauma, including emotional awareness exposure therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy.

Physical movement

Regular movement practice is important to improve the clinical features of fibromyalgia.14 Exercise has been found to modulate pain by affecting various neurotransmitter pathways, including the endogenous cannabinoid and opioid systems, and via the autonomic nervous system by increasing vagal tone.19 Regular exercise results in an improvement in health-related quality of life, physical function, pain, fatigue and stiffness among patients with fibromyalgia.20 There is evidence of significant benefits with regular aerobic exercise, resistance training, flexibility training or a mixture of these in fibromyalgia management.21 However, if deconditioned patients with fibromyalgia initiate exercise sessions of even moderate intensity, there can often be a transient worsening of symptoms. Therefore, the aims and way to begin a regular movement practice must be discussed.

It is important to convey that any gentle activity is helpful, and engaging in a few minutes of an exercise that feels achievable to the patient is often the best starting point.2 Slowly and gradually increasing the amount of exercise over the span of weeks and months usually allows for the best chance of long-term engagement, with a general eventual aim of around 20 minutes at least three times per week. Frequent, brief sessions may sometimes be better tolerated. Walking is usually the most accessible activity to begin with, although gentle movement in a warm swimming pool provides the added benefits of warmth and reduced mechanical impact. Supervised exercise in groups can help provide guidance, reassurance and motivation.13 If patients are significantly deconditioned, then using online classes for chair exercises at home can be useful.

Gentle mind–body movement practices, such as yoga, tai chi or qi gong, are often beneficial in managing fibromyalgia, and are easily added to other multidisciplinary strategies.14,22 These approaches blend the benefits of gentle movement with psychological stress reduction and have been shown to improve pain, sleep and other features of fibromyalgia, albeit often modest changes.23 Chair yoga via online instruction can be an option for people who are unable to undertake the full movements. Tai chi is a martial art and qi gong is a meditative movement practice, both with a significant ability to improve the clinical features of fibromyalgia, including pain, sleep and physical and mental functioning; this may occur by enhancing the patient’s self-regulation and adaptation to pain via increased connectivity of the cognitive control network of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.24-26

Medications

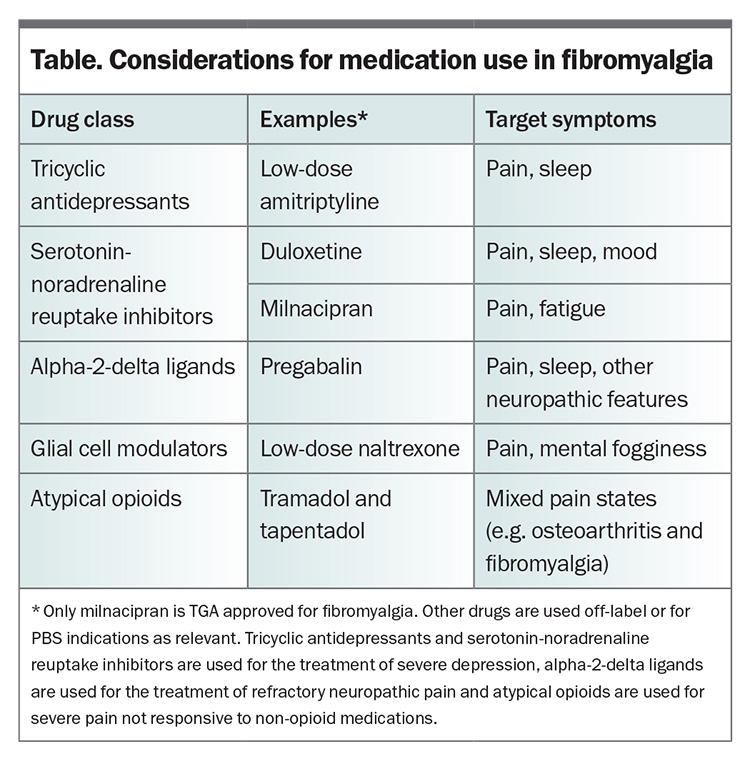

Pharmacotherapy is not the mainstay of fibromyalgia management, but rather, needs to be combined in a multidisciplinary approach with nonpharmacological approaches to achieve the maximum effect. The use of medications that actively target the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia is often limited by modest efficacy, poor tolerance and accessibility issues. There is a 30/50 general rule of thumb wherein 30% of patients derive a 50% improvement from these medications, and 50% of patients experience a 30% improvement. Owing to these limitations, many patients will try other medications that do not have a proven benefit in fibromyalgia management in an attempt to help alleviate their symptoms, sometimes without informing their doctors.27 The choice of medication in patients with fibromyalgia depends on the symptom profile and comorbidities of the patient (Table).28 It is important to start with very low doses of any medication, given that increased central sensitivity often results in chemical and medication intolerances. At low doses, combinations of agents with different modalities can sometimes be utilised with a minimal risk of adverse interactions, although there is limited guiding evidence.29

Simple analgesics

Simple analgesics, such as paracetamol or NSAIDs, are often the first medications tried by people experiencing chronic pain. There are very few published data regarding the benefit in fibromyalgia management with either paracetamol or NSAIDs. However, these medications are easily accessible and often used by people with fibromyalgia to supplement other regular therapies, to manage peripheral sources of pain (e.g. osteoarthritis) or in cases of breakthrough pain. A survey of 1042 patients with fibromyalgia found that 66.1% felt NSAIDs were more effective than paracetamol at alleviating pain.30

Opioids

The use of opioids in the management of fibromyalgia is not recommended.13,31 Patients with fibromyalgia have reduced opioid-mediated descending nociceptive modulation with reduced numbers of available central μ-opioid receptors and higher levels of endogenous opioids in the cerebrospinal fluid.32,33 There is also evidence to suggest that the endogenous opioid system may have a role in the development of fibromyalgia-associated pain and the use of opioid medication in these patients puts them at risk of increased pain due to opioid hyperalgesia.34 There is no robust evidence supporting their use in the very small number of studies that have been published; however, there is a significant associated risk of harm with the potential for adverse effects, opioid hyperalgesia and the potential for addiction and abuse.35,36

Published data supporting the use of atypical opioids such as tramadol and tapentadol in fibromyalgia management are limited.37,38 These agents have serotonergic and noradrenergic activity, as well as µ-opioid binding, so they have some effect on descending antinociceptive central pathways; however, the opioid effects and risks remain problematic.

Serotonin and noradrenaline modulators

The modulation of serotonin and noradrenaline in the descending pain modulatory pathways of the central nervous system by agents such as low-dose tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can improve the clinical features of fibromyalgia independent of their effects on mood.39

Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants

The most commonly used tricyclic antidepressant for fibromyalgia in Australia remains amitriptyline. It is best used at low doses, starting at 5 mg in the evenings and rarely prescribed at doses greater than 50 mg unless needed for antidepressant purposes. There is usually an improvement in pain, sleep, fatigue and quality of life with treatment; however, the supporting studies are short term and report modest gains of only 15 to 20% above those of placebo.40

Serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

SNRIs are widely used for the management of fibromyalgia. Duloxetine has a slightly more serotonergic effect and can be helpful for sleep and pain. Milnacipran is more activating with a higher adrenergic influence; however, although it is TGA approved for use in fibromyalgia, it is no longer available locally and needs to be imported. SNRI agents show a modest improvement in pain and global impression of change.41,42 Duloxetine has a beneficial effect in fibromyalgia that is independent of an effect on mood.43 However, the use of these agents, which might also include venlafaxine, is advantageous if there is coexisting depression or anxiety.41 Adverse effects, such as headache, palpitations, nausea and flushing, often occur when used at higher doses.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) modulate serotonergic pathways alone, without noradrenergic effects. Although this is effective for mood, there seems to be less of a benefit for pain. There is inconsistent and often low-quality evidence for the use of SSRIs in fibromyalgia management other than for an improvement in depression.44

Membrane stabilisers

Pregabalin and gabapentin bind to voltage-dependent calcium channels and reduce central neuron sensitivity. They are widely used for the management of chronic pain, and the use of pregabalin in patients with fibromyalgia is supported by clinically relevant improvements in pain, sleep and quality of life.45,46 The evidence is less robust for gabapentin. Many patients are unable to tolerate the highest recommended doses of pregabalin or gabapentin, and this can limit their use to low doses. Initiating pregabalin at a dose of 25 mg in the evening is often enough to help with some pain and sleep improvement, without side effects such as dizziness, somnolence, fatigue, sedation, weight gain, peripheral oedema and ataxia.47

Low-dose naltrexone

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist; however, at low doses between 1 mg and 4.5 mg, it follows alternative pharmacological pathways resulting in both analgesic and neuro-immunomodulatory effects. The transient blockade of opioid receptors leads to a feedback upregulation of endogenous opioid signalling, resulting in analgesia.48 At these low doses, it also acts to inhibit microglial activation by binding to toll-like receptor 4, inhibiting the downstream cellular signalling pathways that lead to the release of proinflammatory cytokines.49

The body of published evidence is currently limited by small sample sizes; however, improvements in pain and wellbeing are regularly reported.50,51 In a recent study, the reduction in pain was not statistically significant in the overall group, although there was evidence for an improvement in memory.52 Further investigation is ongoing; however, mild, infrequent adverse effects may occur, and in patients who are responsive, naltrexone can be a helpful, safe agent. Clinically, the most effective doses vary between individuals, often between 1 and 6 mg per day, and it is best to start with small doses in the evening and titrate upwards.53 These low doses need to be ordered through a compounding pharmacy in Australia, which can add to costs. Low-dose naltrexone should be ceased for surgery unless it is minor or under local anaesthesia or not requiring opioids (e.g. eye surgery or colonoscopy).

Cannabinoids

The use of cannabinoids for the management of fibromyalgia cannot be recommended at this time. The endocannabinoid system plays an important role in pain and stress modulation; however, fibromyalgia clinical trials published thus far have had distinct limitations in methodology, and longitudinal studies are needed to fully assess their efficacy and tolerability.54 Despite these reservations, the prescription of medical cannabis for chronic pain in Australia is rapidly increasing, with applications through the Authorised Prescriber pathway increasing from 2160 in 2020 to 18,825 by December 2024.55 A large Australian survey of people who use mainly prescribed (73%) and illicit cannabis found that 37% were using them to help with symptoms of chronic pain and the prescribed doses were ingested mostly via oral or vaporised routes. Ninety-seven percent of respondents reported an improvement in their symptoms, with the most common side effects of dry mouth, increased appetite, drowsiness, eye irritation and memory problems mostly reported as mild.56

If cannabinoids are to be used, prescribed medical cannabis offers more regulated access to agents with more reliable formulations, with less reported side effects that are used in less harmful ways. Medical cannabis also may be pragmatically useful in helping patients with fibromyalgia reduce dependence on opioids and benzodiazepines.57

Concurrent issues

Comorbid conditions are common in patients with fibromyalgia and can often add to clinical problems or augment the features of fibromyalgia. It is important to actively assess for any contributions to symptom burden from commonly found comorbidities. Sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, endocrine dysfunction and perimenopause all need to be considered as potential influences on clinical state and managed accordingly. Other associated chronic overlapping pain conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular disorder or migraine, may need additional treatments.

The presence of peripheral generators of chronic pain such as osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis can continue to stimulate peripheral nociceptive input to central pain pathways, leading to the perpetuation of the chronic nociplastic pain processes in fibromyalgia. Adequate management of evident peripheral pain can ameliorate the overall central pain severity.

The psychosocial milieu of patients also has a profound influence on the efficacy of any management program. It is difficult to influence clinical features if there are continued significant stressors driving top-down central sensitivity. Practical or financial difficulties can also result in an inability to access therapies.

Flare-ups

Fibromyalgia is a dynamic condition, with variable levels of baseline symptoms that can sometimes increase in severity, known as flare-ups. Stress factors and poor sleep are common triggers for flare-ups and must be recognised and addressed through patient-directed techniques, such as relaxation, intensification of background mind–body approaches and gentle physical movement techniques. Regular dosing of simple analgesics and avoidance of opioid analgesics at these times is important. Adjustment of pain-modulatory medications can be useful, depending on the background dose. During flare-ups, patients often use additional physical techniques that have been useful previously. Severe psychological distress, if present, also needs to be addressed. The support of the treating clinician during flare-ups, through validation of symptoms, education and simple practical advice, is a powerful and important aspect of management.

Conclusion

The management of fibromyalgia remains the most effective as a multidisciplinary approach. The most effective change is made when patients have high levels of engagement and are proactive in their self-management strategies. There are new ways available of delivering some psychological therapeutic approaches, and a better awareness that any level of gentle, frequent movement practice can have benefit. As we further understand pathophysiological nuances, pharmacological approaches may provide improved symptom control; however, medications currently remain the most effective when used together with nonpharmacological strategies. PMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Littlejohn G, Guymer E. Neurogenic inflammation in fibromyalgia. Semin Immunopathol 2018; 40: 291-300.

2. Clauw DJ. From fibrositis to fibromyalgia to nociplastic pain: how rheumatology helped get us here and where do we go from here? Ann Rheum Dis 2024; 83: 1421-1427.

3. Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JWS, Rief W, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain 2019; 160: 28-37.

4. Kosek E, Cohen M, Baron R, et al. Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states? Pain 2016; 157: 1382-1386.

5. Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, Littlejohn G, Usui C, Hauser W. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet 2021; 397: 2098-2110.

6. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33: 160-172.

7. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016; 46: 319-329.

8. Clauw DJ. Why don’t we use a body map in every chronic pain patient yet? Pain 2024 Feb 1; e-pub (https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003184).

9. Thiagarajah AS, Guymer EK, Leech M, Littlejohn GO. The relationship between fibromyalgia, stress and depression. Int J Clin Rheumatol 2014; 4: 371-384.

10. Wolfe F. Fibromyalgianess. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 715-716.

11. Kang Y, Trewern L, Jackman J, McCartney D, Soni A. Chronic pain: definitions and diagnosis. BMJ 2023; 381: e076036.

12. Mann EG, Lefort S, Vandenkerkhof EG. Self-management interventions for chronic pain. Pain Manag 2013; 3: 211-222.

13. Carville S, Constanti M, Kosky N, Stannard C, Wilkinson C; Guideline Committee. Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2021; 373: n895.

14. Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. Noninvasive nonpharmacological treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review update. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020.

15. Bernardy K, Klose P, Welsch P, Hauser W. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of cognitive behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain 2018; 22: 242-260.

16. Nascimento SS, Oliveira LR, DeSantana JM. Correlations between brain changes and pain management after cognitive and meditative therapies: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Complement Ther Med 2018; 39: 137-145.

17. Catella S, Gendreau RM, Kraus AC, et al. Self-guided digital acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia management: results of a randomized, active-controlled, phase II pilot clinical trial. J Behav Med 2024; 47: 27-42.

18. Bernardy K, Klose P, Welsch P, Hauser W. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of internet-delivered psychological therapies for fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain 2019; 23: 3-14.

19. Da Silva Santos R, Galdino G. Endogenous systems involved in exercise-induced analgesia. J Physiol Pharmacol 2018; 69: 3-13.

20. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, et al. Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 6: CD012700.

21. Bidonde J, Boden C, Foulds H, Kim SY. Physical activity and exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. In: Ablin JN, Shoenfeld Y, eds. Fibromyalgia syndrome. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature; 2021. p. 59-72.

22. Bravo C, Skjaerven LH, Guitard Sein-Echaluce L, Catalan-Matamoros D. Effectiveness of movement and body awareness therapies in patients with fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2019; 55: 646-657.

23. Sutar R, Yadav S, Desai G. Yoga intervention and functional pain syndromes: a selective review. Int Rev Psychiatry 2016; 28: 316-322.

24. Sawynok J. Benefits of tai chi for fibromyalgia. Pain Manag 2018; 8: 247-250.

25. Sawynok J, Lynch ME. Qigong and fibromyalgia circa 2017. Medicines (Basel) 2017; 4: 37.

26. Kong J, Wolcott E, Wang Z, et al. Altered resting state functional connectivity of the cognitive control network in fibromyalgia and the modulation effect of mind-body intervention. Brain Imaging Behav 2019; 13: 482-492.

27. Warren Z, Guymer E, Mezhov V, Littlejohn G. Significant use of non-evidence-based therapeutics in a cohort of Australian fibromyalgia patients. Intern Med J 2024; 54: 568-574.

28. Farag HM, Yunusa I, Goswami H, Sultan I, Doucette JA, Eguale T. Comparison of amitriptyline and US Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5: e2212939.

29. Thorpe J, Shum B, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Gilron I. Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 2: CD010585.

30. Wolfe F, Zhao S, Lane N. Preference for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs over acetaminophen by rheumatic disease patients: a survey of 1,799 patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43: 378-385.

31. Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 318-328.

32. Harris RE, Clauw DJ, Scott DJ, McLean SA, Gracely RH, Zubieta JK. Decreased central muopioid receptor availability in fibromyalgia. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 10000-10006.

33. Baraniuk JN, Whalen G, Cunningham J, Clauw DJ. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of opioid peptides in fibromyalgia and chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2004; 5: 48.

34. Schrepf A, Harper DE, Harte SE, et al. Endogenous opioidergic dysregulation of pain in fibromyalgia: a PET and fMRI study. Pain 2016; 157: 2217-2225.

35. Sorensen J, Bengtsson A, Backman E, Henriksson KG, Bengtsson M. Pain analysis in patients with fibromyalgia. Effects of intravenous morphine, lidocaine, and ketamine. Scand J Rheumatol 1995; 24: 360-365.

36. Gaskell H, Moore RA, Derry S, Stannard C. Oxycodone for pain in fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 9: CD012329.

37. Russell IJ, Kamin M, Bennett RM, Schnitzer TJ, Green JA, Katz WA. Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol 2000; 6: 250-257.

38. Baron R, Eberhart L, Kern KU, et al. Tapentadol prolonged release for chronic pain: a review of clinical trials and 5 years of routine clinical practice data. Pain Pract 2017; 17: 678-700.

39. Perrot S, Javier RM, Marty M, Le Jeunne C, Laroche F. Antidepressant use in painful rheumatic conditions. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2008; 34: 433-453.

40. Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M, Calandre EP. Amitriptyline for the treatment of fibromyalgia: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Neurother 2015; 15: 1123-1150.

41. Welsch P, Uceyler N, Klose P, Walitt B, Hauser W. Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 2: CD010292.

42. Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Eschweiler J, Baroncini A, Bell A, Colarossi G. Duloxetine for fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2023; 18: 504.

43. Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain 2005; 119: 5-15.

44. Walitt B, Urrutia G, Nishishinya MB, Cantrell SE, Hauser W. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 2015: CD011735.

45. Arnold LM, Choy E, Clauw DJ, et al. An evidence-based review of pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Curr Med Res Opin 2018; 34: 1397-1409.

46. Hauser W, Bernardy K, Uceyler N, Sommer C. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with gabapentin and pregabalin – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain 2009; 145: 69-81.

47. Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M. Alpha(2)delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use. Expert Rev Neurother 2016; 16: 1263-1277.

48. Wang D, Sun X, Sadee W. Different effects of opioid antagonists on mu-, delta-, and kappa-opioid receptors with and without agonist pretreatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007; 321: 544-552.

49. Trofimovitch D, Baumrucker SJ. Pharmacology update: low-dose naltrexone as a possible nonopioid modality for some chronic, nonmalignant pain syndromes. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019; 36: 907-912.

50. de Carvalho JF, Skare T. Low-Dose naltrexone in rheumatological diseases. Mediterr J Rheumatol 2023; 34: 1-6.

51. Aitcheson N, Lin Z, Tynan K. Low-dose naltrexone in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Aust J Gen Pract 2023; 52: 189-195.

52. Due Bruun K, Christensen R, Amris K, et al. Naltrexone 6 mg once daily versus placebo in women with fibromyalgia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatol 2024; 6: e31-e39.

53. Marcus NJ, Robbins L, Araki A, Gracely EJ, Theoharides TC. Effective doses of low-dose naltrexone for chronic pain – an observational study. J Pain Res 2024; 17: 1273-1284.

54. Bourke SL, Schlag AK, O’Sullivan SE, Nutt DJ, Finn DP. Cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system in fibromyalgia: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Pharmacol Ther 2022; 240: 108216.

55. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medicinal cannabis Authorised Prescriber Scheme data. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved-therapeutic-goods/medicinal-cannabis-hub/medicinal-cannabis-access-pathways-and-usage-data/medicinal-cannabis-authorised-prescriber-scheme-data (accessed December 2024).

56. Mills L, Arnold JC, Suraev A, et al. Medical cannabis use in Australia seven years after legalisation: findings from the online Cannabis as Medicine Survey 2022-2023 (CAMS-22). Harm Reduct J 2024; 21: 104.

57. Boehnke KF, Gagnier JJ, Matallana L, Williams DA. Substituting cannabidiol for opioids and pain medications among individuals with fibromyalgia: a large online survey. J Pain 2021; 22: 1418-1428.